シンボライズするにあたっての一考察

今回のプロジェクトの象徴を視覚化するにあたり、絡み合うものが大まかに三点ある。

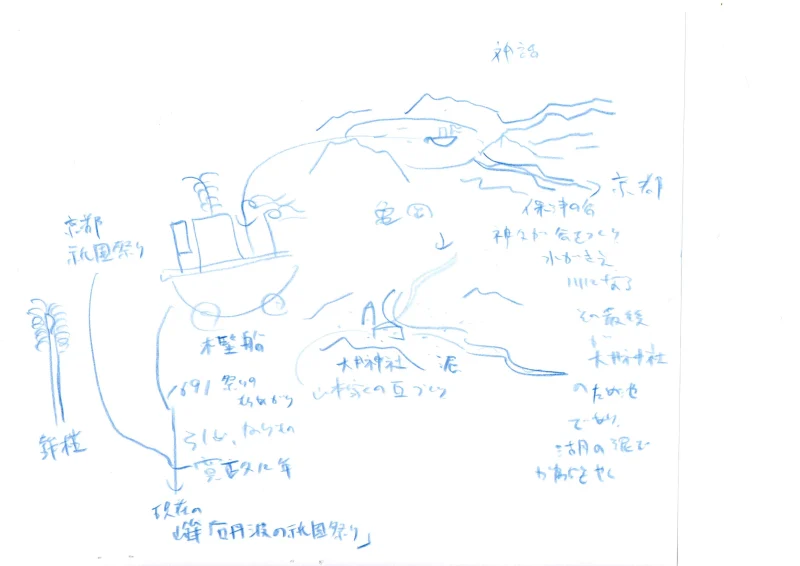

一つは、地理的要因から発生した亀岡の文化とその流れである。

二つ目は、オーナーである山本氏の家業であった瓦造りや、その工場と住宅群である。

三つ目は、本プロジェクトの流れである。

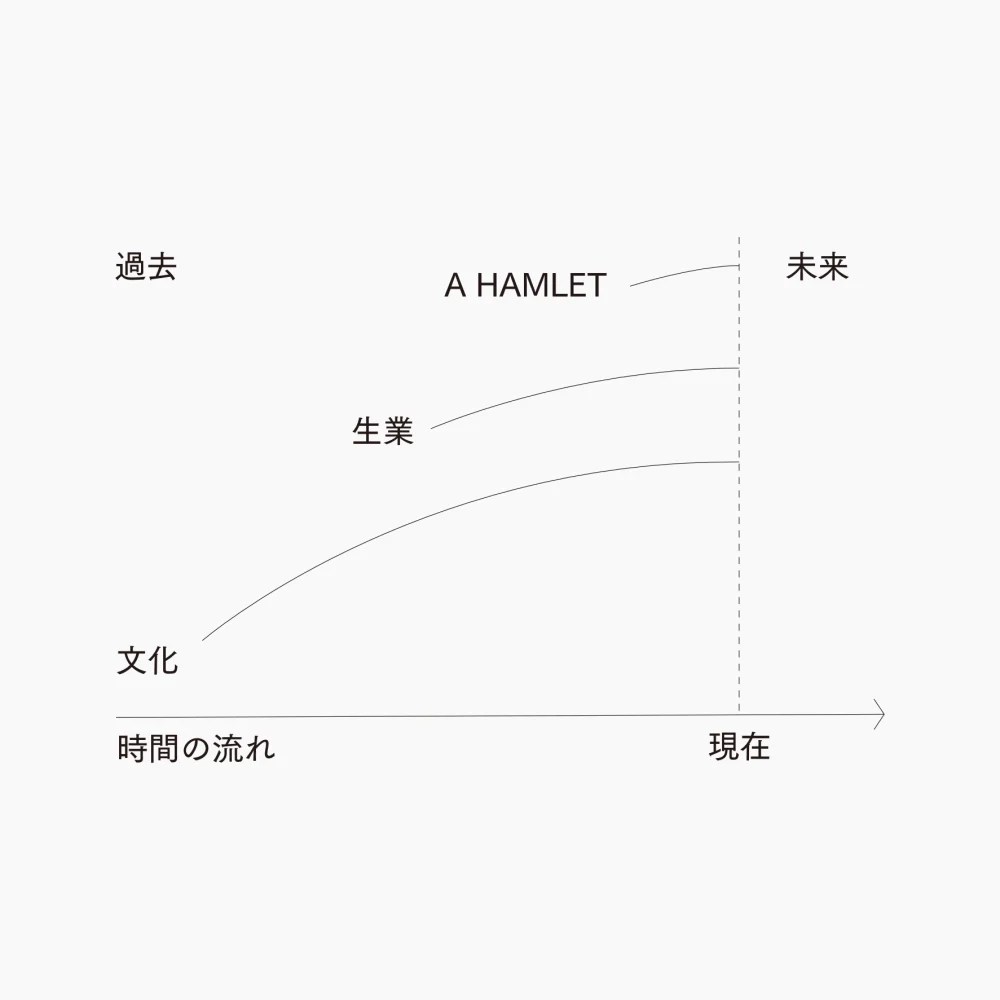

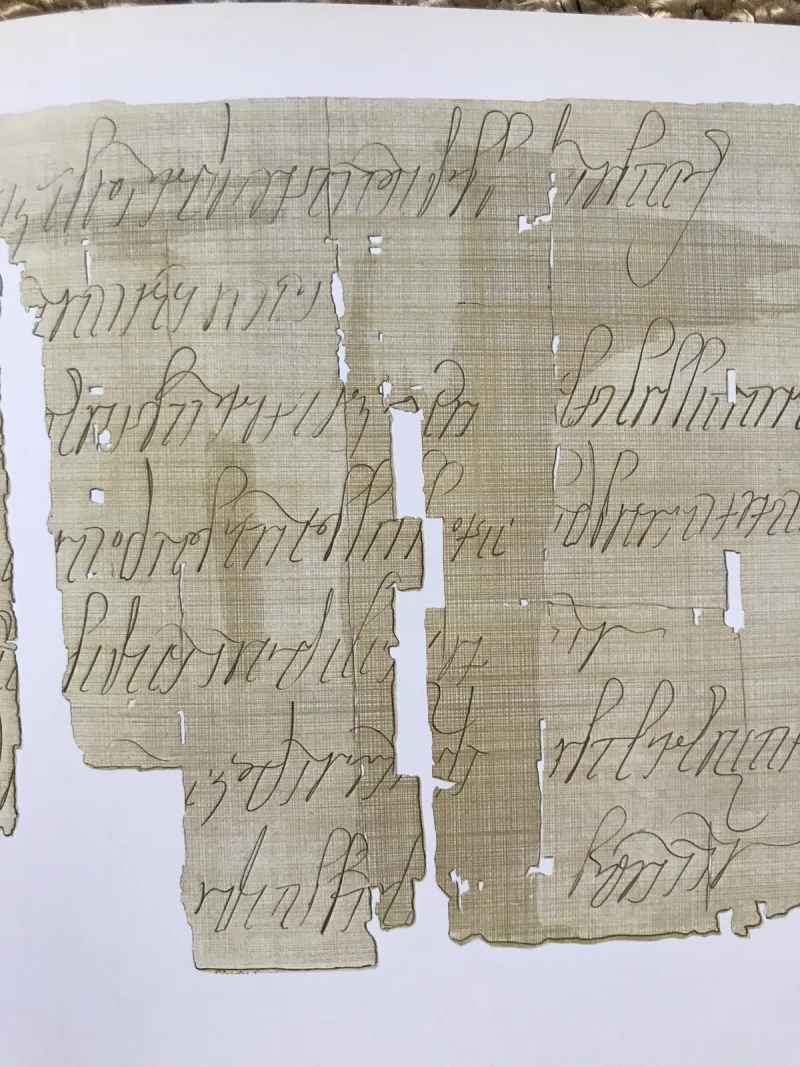

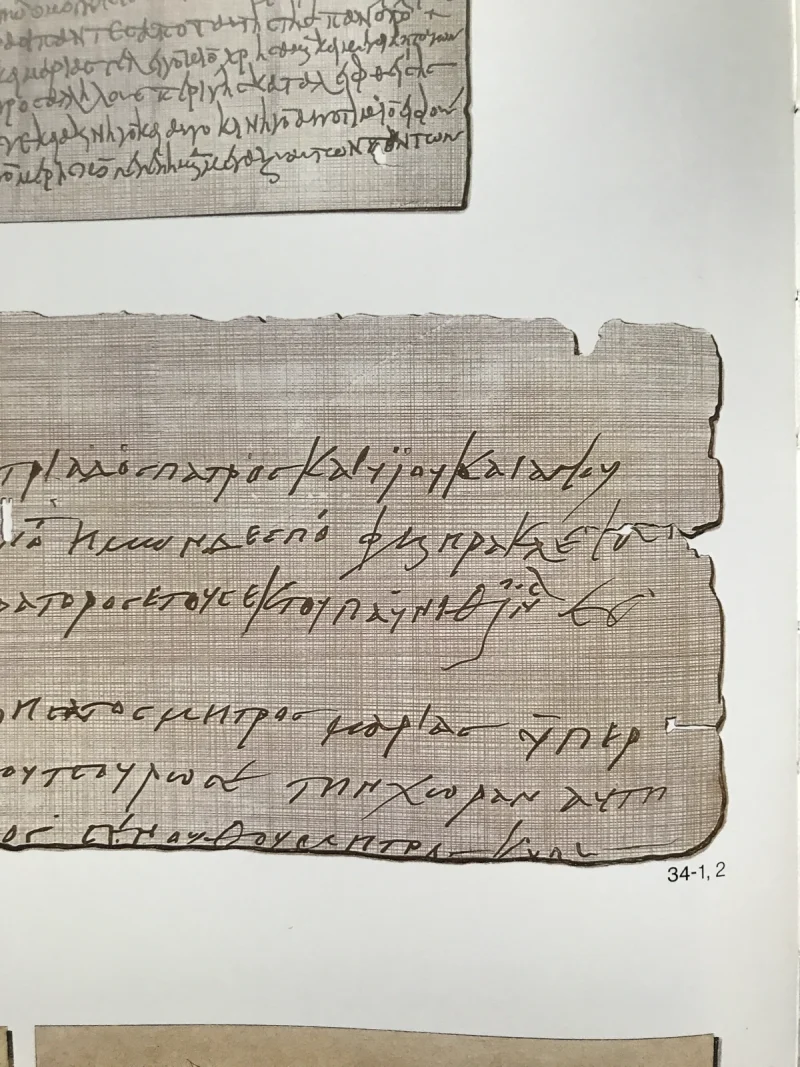

一つ目から順に時代は現代へと近づいていく〈Fig.1〉。また視点を変え、住宅群が建つ土地を断面で見ると、これらが重なっているイメージになる〈Fig.2〉。

人の営みは誰かが投げたボールのようなもので、いつからか始まり、時間とともに軌跡を描きながらどこかへ向かっていく。私たちが生きている「今」はそのエッジ(先端)であり、この先がどうなるのか、またどうあるべきかは、過去の流れから推察するしかない。

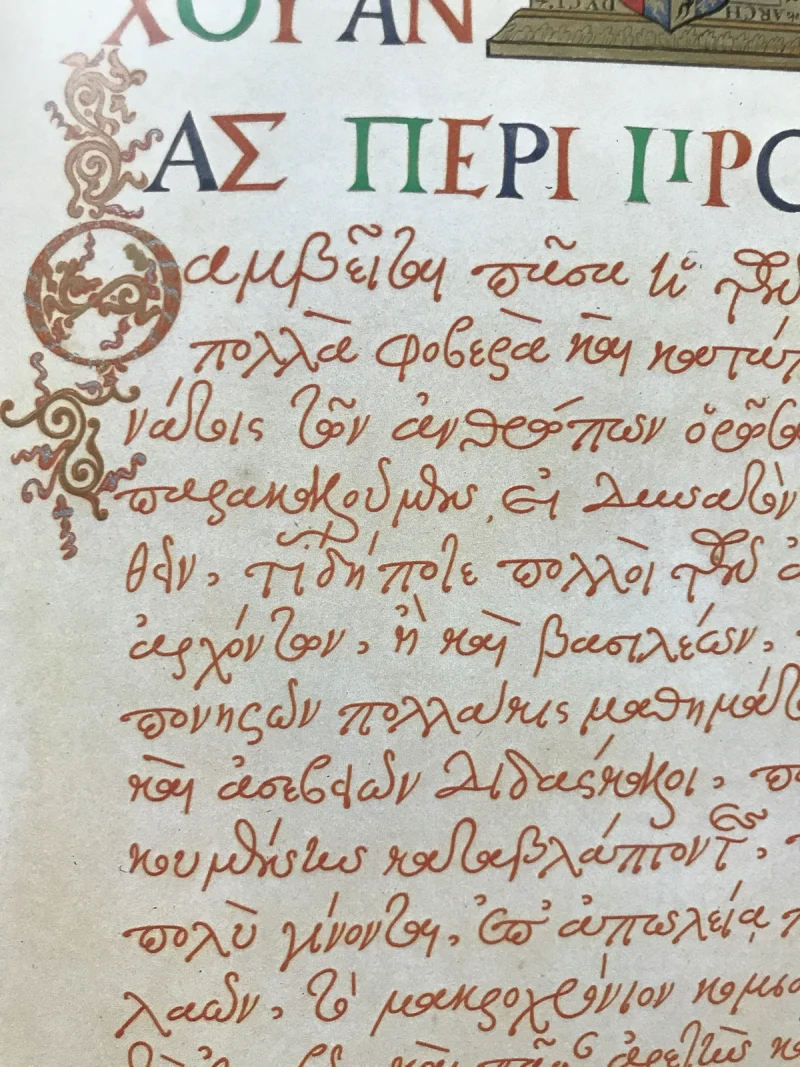

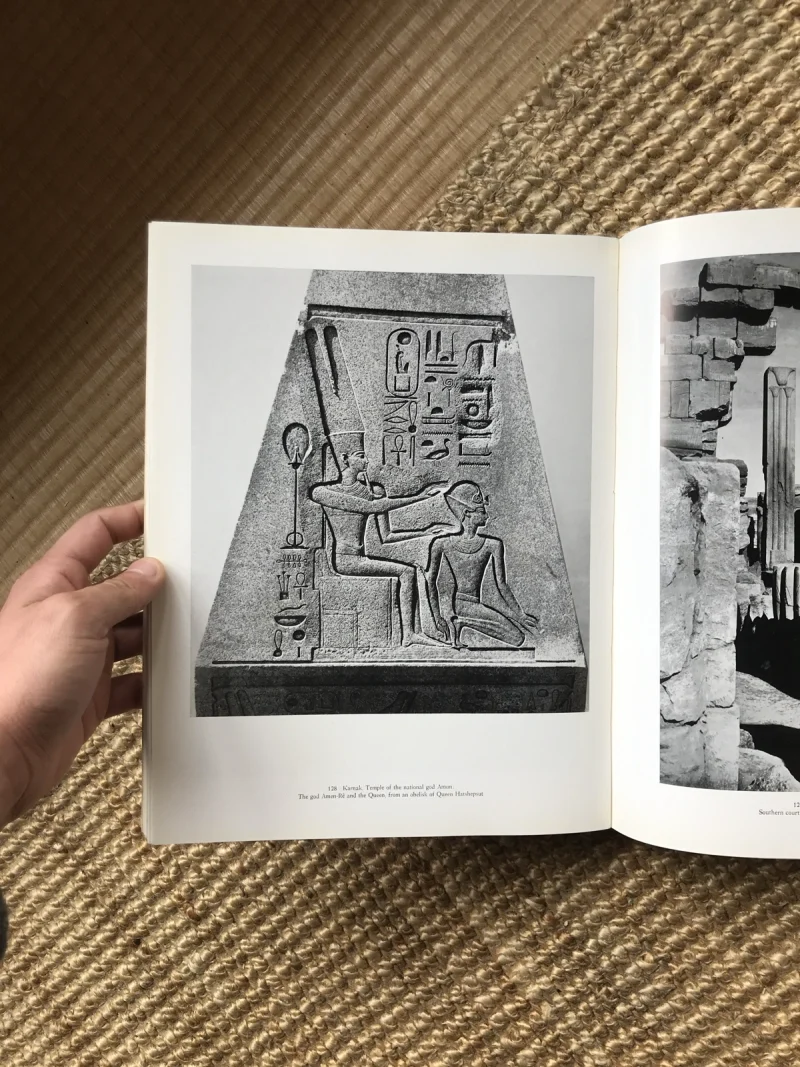

過去を振り返ると〈Fig.2〉、異なる文化・宗教・政治思想などが住民の上に覆いかぶさることは往々にして起こる。ただ重要なのは、それが暴力的に支配するのか、作法をもって配慮を尽くすのかという点である。日本の民話や神話に見られる新しい神の誕生譚にもその痕跡がある。マレビト(客人)と呼ばれる遠方から来た神は、大陸から流刑となり日本に渡ってきた知識人であったと思われる。彼らがこの地に住むとき、土着の神から問いかけを受け、贈り物や歌で応答すると、その娘(女神)を娶り、子をもうけるという話が数多く残っている。こうして他民族と混じり合うことで、祖先たちは機織りの技術や本草学、暦、火薬、製鉄などを獲得したと考えられる。

A HAMLETにおいて、私たちは覆いかぶさる側である。すでにそこに住んでいた人や土地の民俗と良い形で交わり、新しい文化が立ち上がることが望ましい。それはまた、私自身の問題意識とも重なっている。すなわち「デザイン」という翻訳されていない横文字を、経済ではなく文化とどう接続するかという問いである。

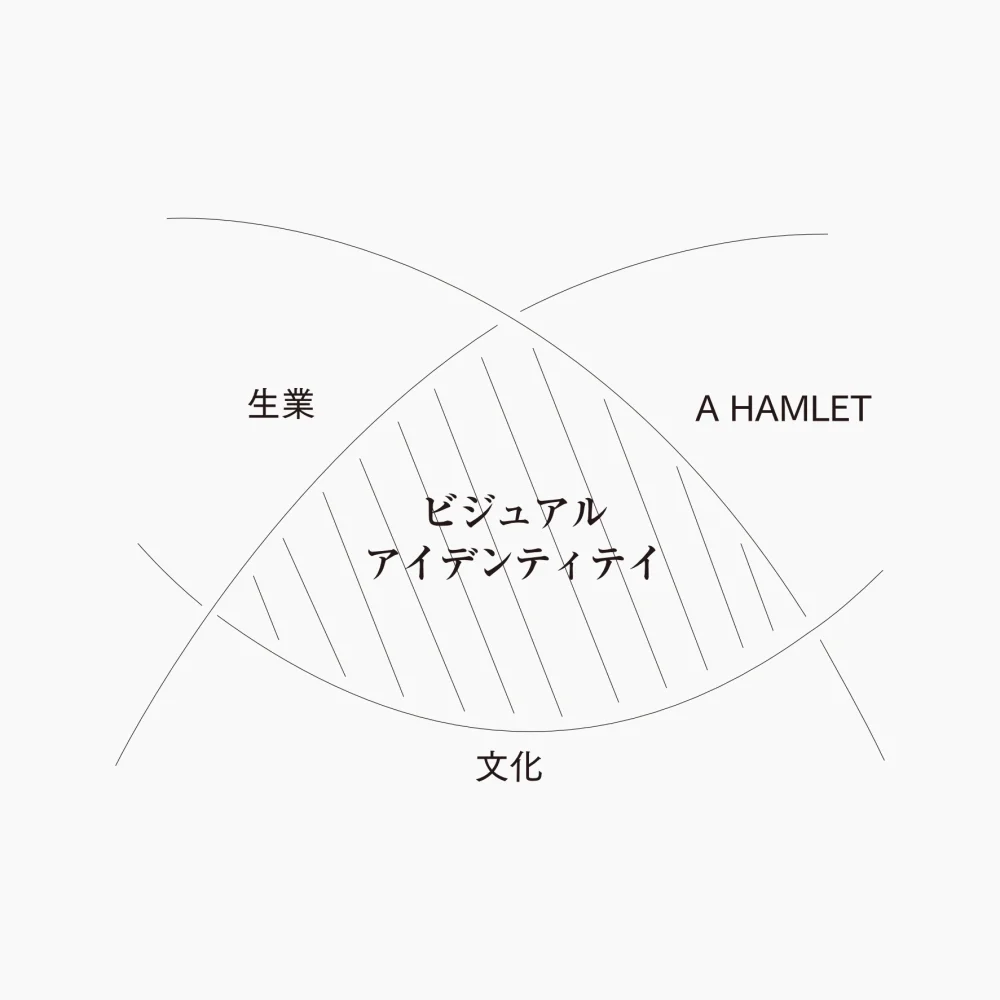

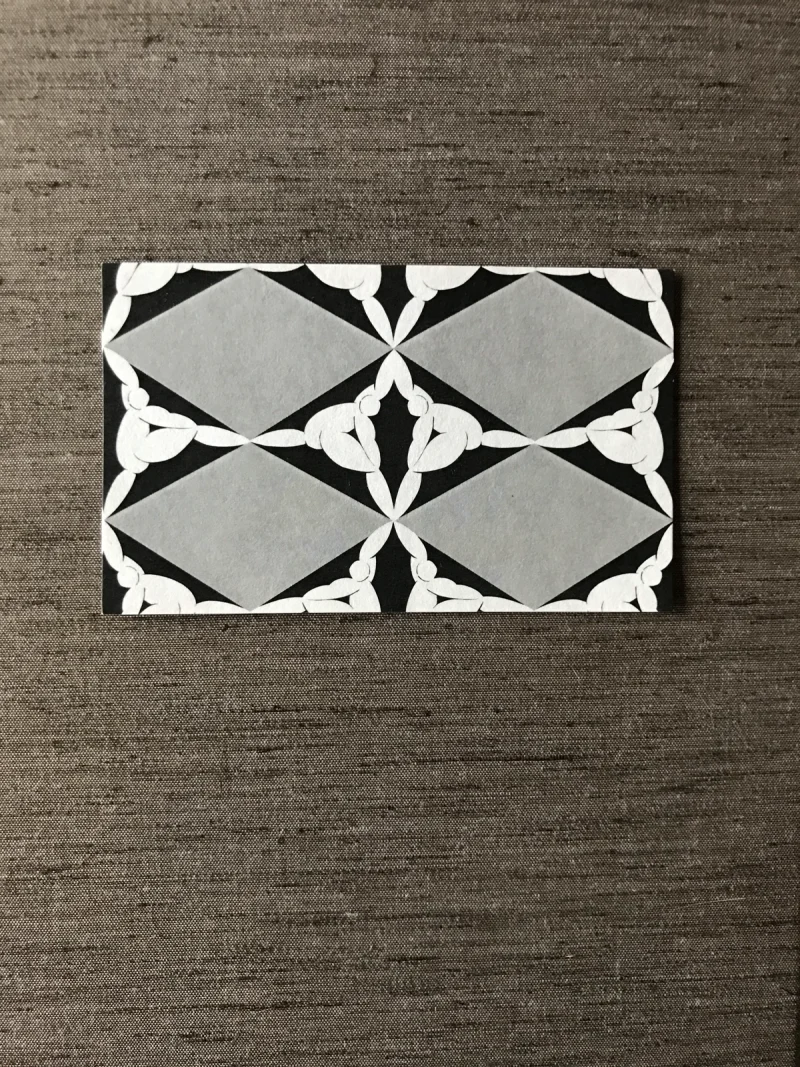

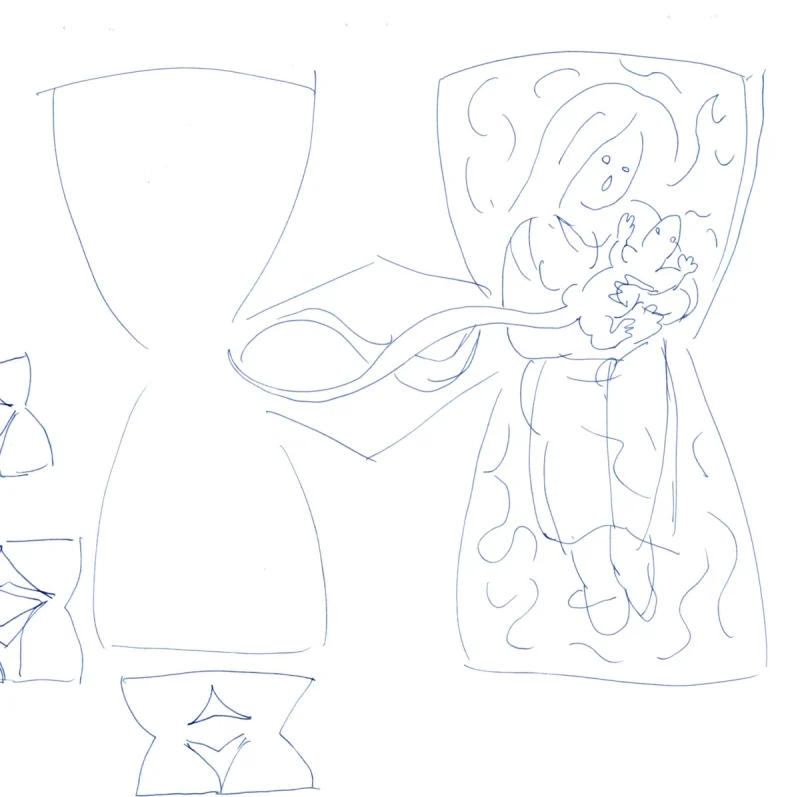

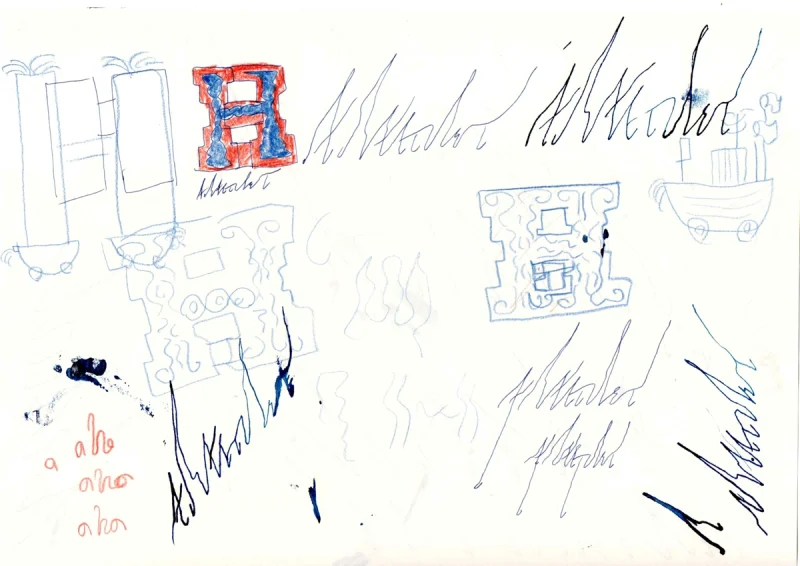

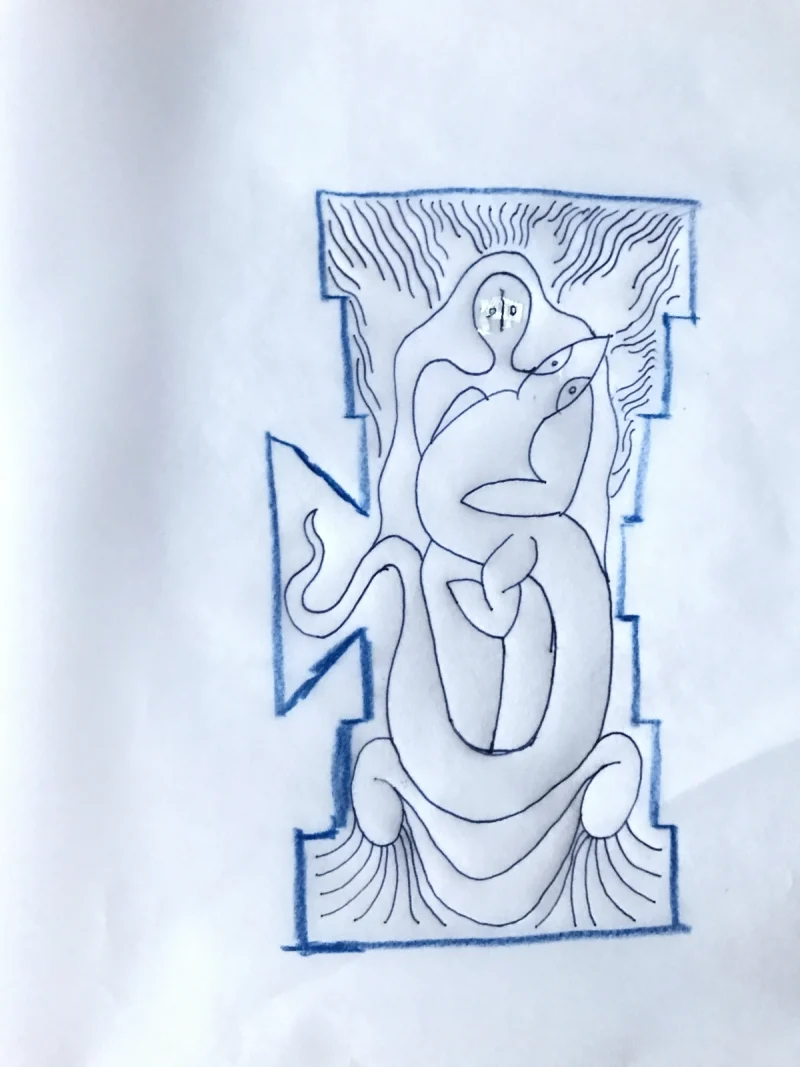

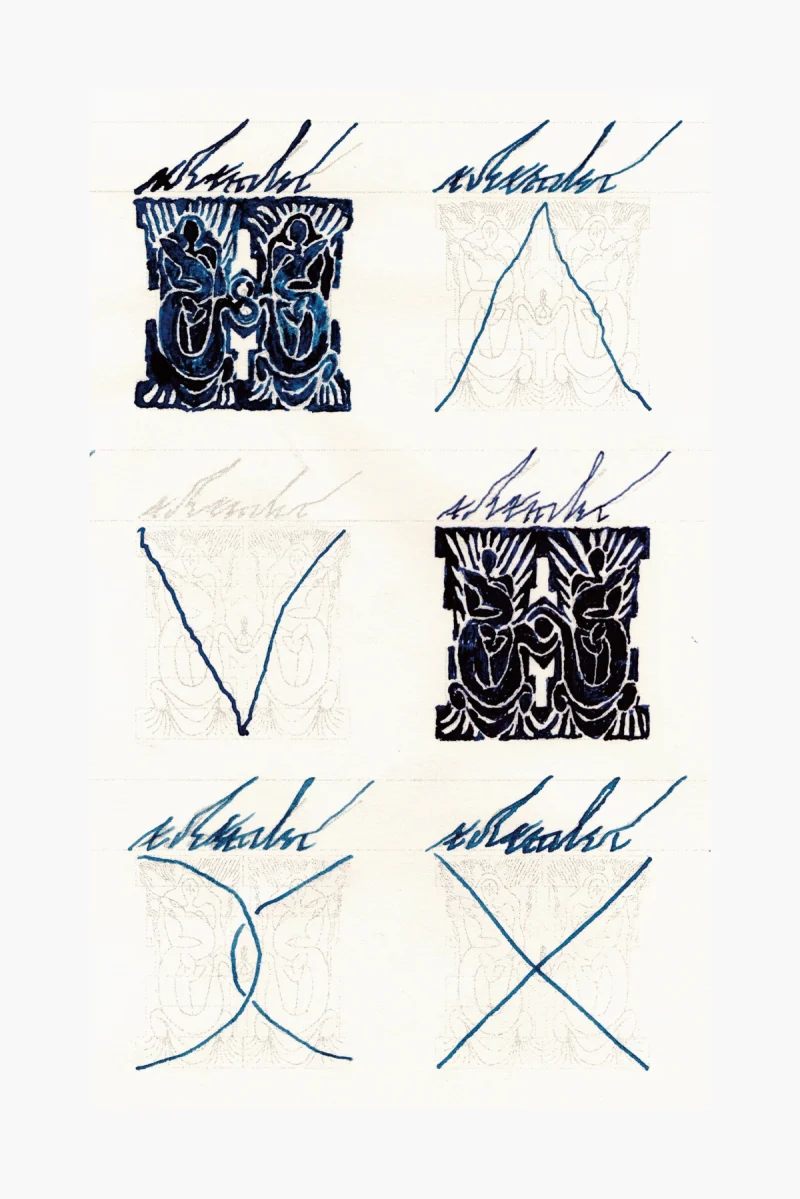

その手法として、冒頭の三本のラインのエッジを掴み、互い違いに組み合わせることで視覚的象徴を作る。ヒントとなるのは編組細工である。アケビの蔓でアワジ結びを作るように、二本の蔓を上下に組み合わせていくと、ばらばらで解けやすかったラインがある瞬間にカチッと固定され、面が立ち上がる。そのようにしてイメージ(図像)を形づくる〈Fig.3〉。

先行事例である琥珀街を訪れた際、川端氏(本プロジェクトのオーナーの一人で不動産業)が「不動産は、建物に利用者が入るとガラッと姿を変える」と語っていた。建物は施工が完了した時点で完成とされるが、入居者によって全く異なる使い方をされ、それが内装や外構に滲み出る。そして集合住宅では、入居者同士の関係性がそのコミュニティの性格を決定する。マンションの管理組合のように閉じたものになるか、琥珀街のように自治的な雰囲気を持つかは、建物の質と住人の関係性に左右される。これを不動産的に設計可能かと問えば、容易に再現できるものではない〈FW01〉〈FW02〉。

一方、瓦造りは土を採集・精製し、水を加えて練り、粘土として成形・乾燥させる。そのままでは脆く、雨に打たれればすぐに溶けてしまうが、炎で焼くことで硬く締まり、水を弾く瓦となる。現場を案内された際、住宅が瓦用の土を採取したため土地が低くなっていること、屋根の頂の瓦が同じ粘土で留められていること、瓦の波模様や屋号の印を見せてもらった。驚いたのは、オーナーの山本氏自らが施工に参加していたことである。解体時には屋根や壁の粘土を剥がし、廃棄せず再精製して素材として再利用する。外構には小さな林が作られ、火床が設けられ、その受け皿には瓦の粘土が敷かれていた。私も現場を訪れた際に工事に加わり、わずかではあるがA HAMLETの施工に参加した。オーナー自らが工事に関わり、土地の土や瓦造りの要素を用いることが、土地・生業・プロジェクトをつなげているように思えた。

不動産と瓦造りを照らすと、建物は焼く前の瓦に似ている。土と水で形を作り乾かしただけの瓦が水で溶けてしまうように、建物もそれだけでは成立しない。「住む」「飼う」「祀る」といった目的があって建てられ、人や何かが使い始めることで場は変性し、別のものになる。焼く前の瓦が炎で性質を変えるように、建物は利用する者によって変性する。すなわち粘土は建物であり、炎は利用者である〈Fig.5〉。さらに、瓦を作る期間よりも屋根の上で雨を防ぐ時間が長いように、建築も建てられた後、人が住む時間の方が長い。家主が居なくなっても子や他者が修繕しつつ住み続ける。誰が住むかによって家の価値やコミュニティの質は大きく変わり、その調整が長く続く。それは「火の管理」に似ている。私は「火の管理」を通してこのプロジェクトを考えられるのではないかと思った。

山形県置賜地方の民話「鼠浄土」には「火もらい婆」という言葉が登場する。これは「おむすびころりん」の原型で、全国に多くのバリエーションがある。その中で「火もらい婆」とは、自宅の囲炉裏の火を消してしまい、隣家に火をもらいに行く駄目な婆のことである。昔は火を新しく起こすのが大変で、外出や就寝時には火を小さく保ち、決して消さず、戻れば増幅させて暖や煮炊きに使っていた。火を管理できないことは大きな失態とされた。

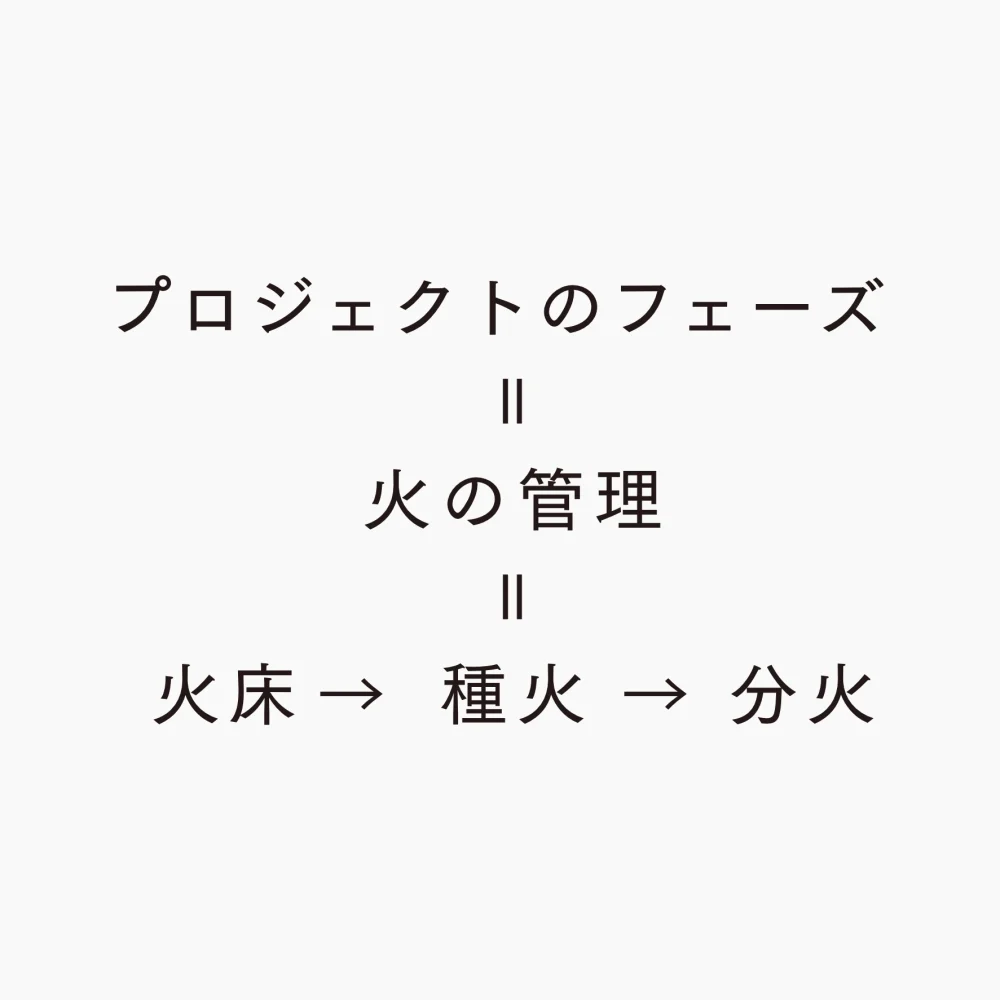

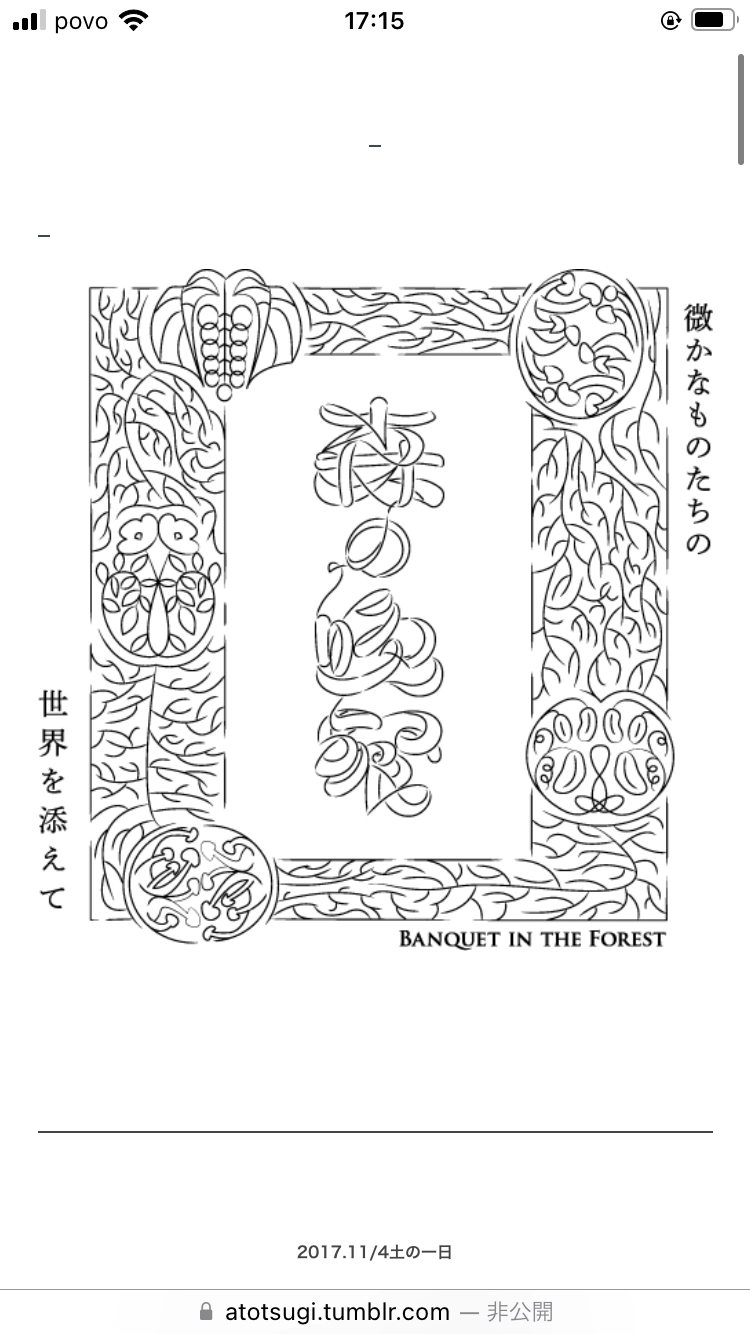

A HAMLETにおいては、オーナーたちが火の管理、つまり住人やコミュニティの関係性を調整する役割を担うが、住人にも火の管理の素養が求められる。店を営んだり住んだりする中で、自分のことだけでなくA HAMLET全体を考え、明かりを灯し続けることが必要だ。そのため利用者と運営者の共通言語として「火」をシンボライズすることが望ましい。建物・メディア・ビジュアルアイデンティティを作ることは「火床」を設け「種火」を灯すことであり、やがて「分火」というフェーズへ進むだろう。現在の関係者が灯した種火が増幅し、住人が去ると同時に火が移る可能性や、火を絶やし「火もらい婆」となった人が新しい火を求めに来ることもある。その際、建物やメディア、ビジュアルアイデンティティはどうあるべきかを「火の管理」の観点から考えていく〈Fig.6〉。

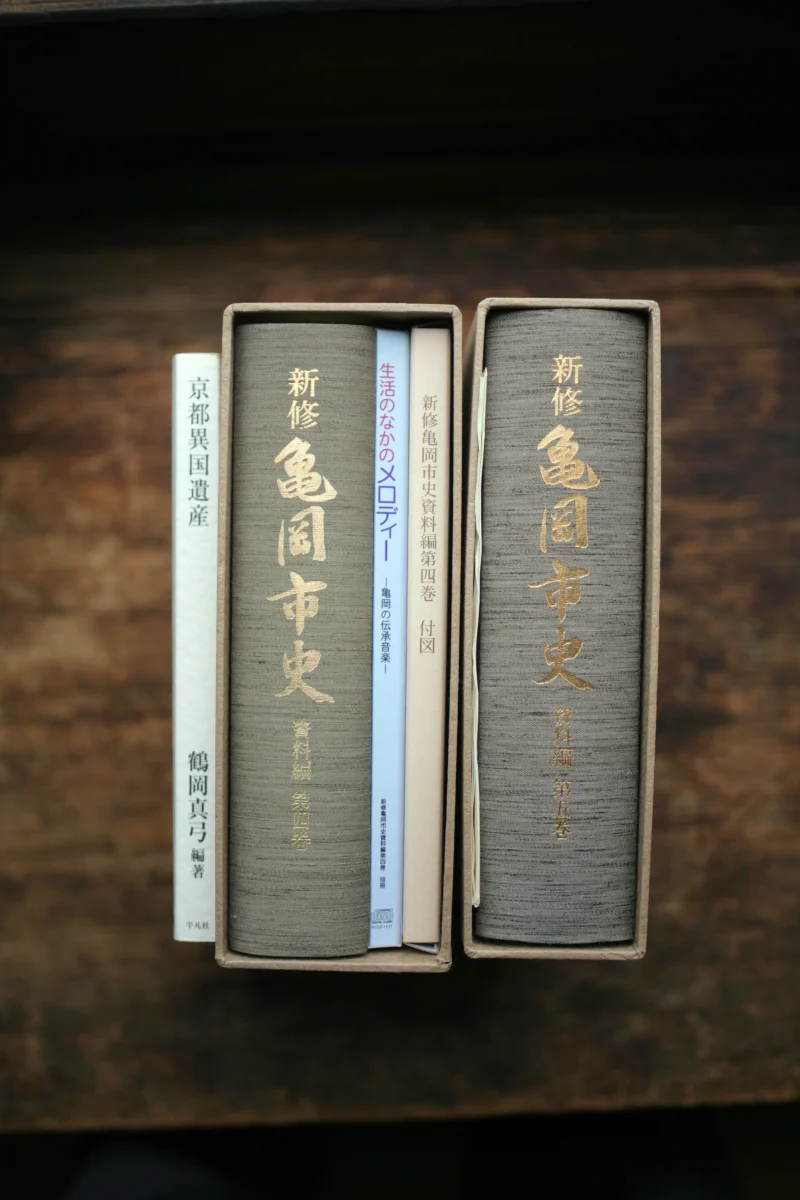

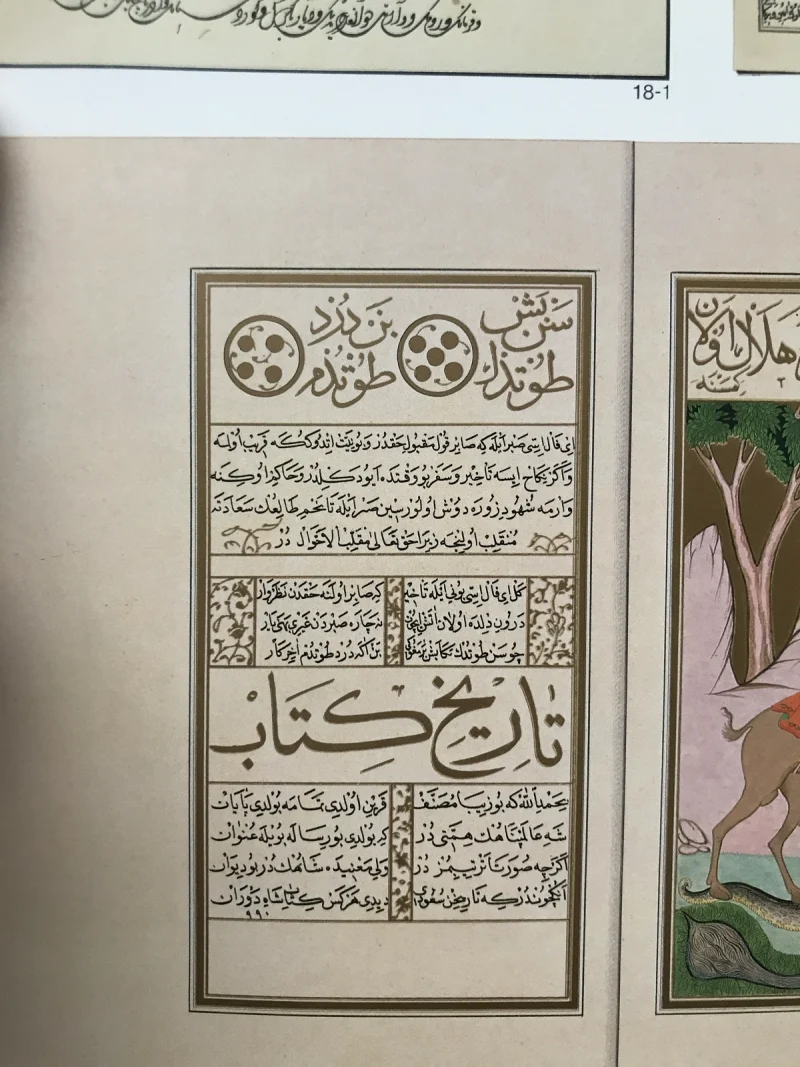

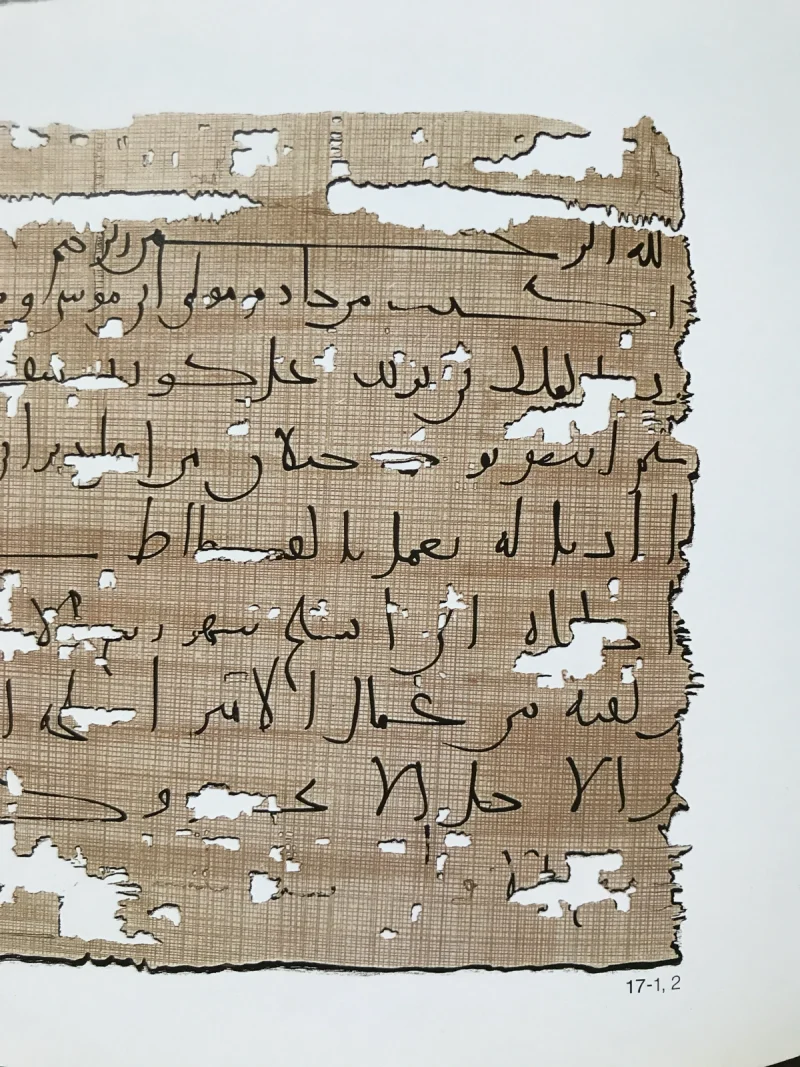

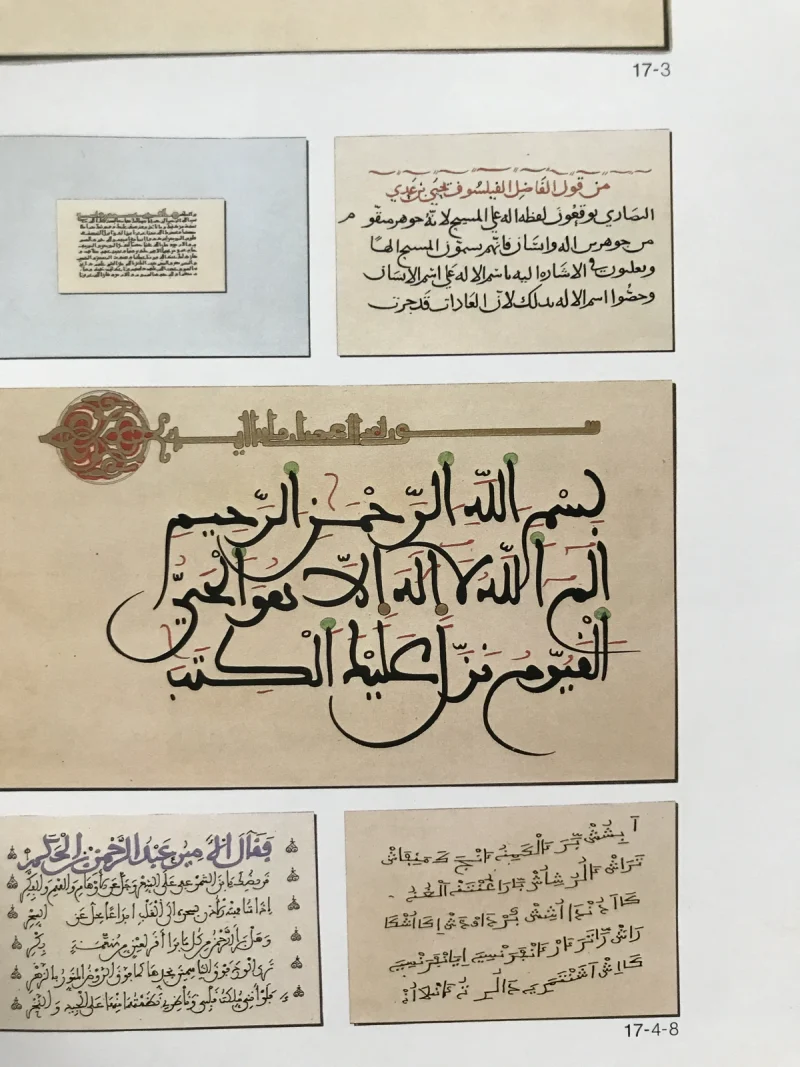

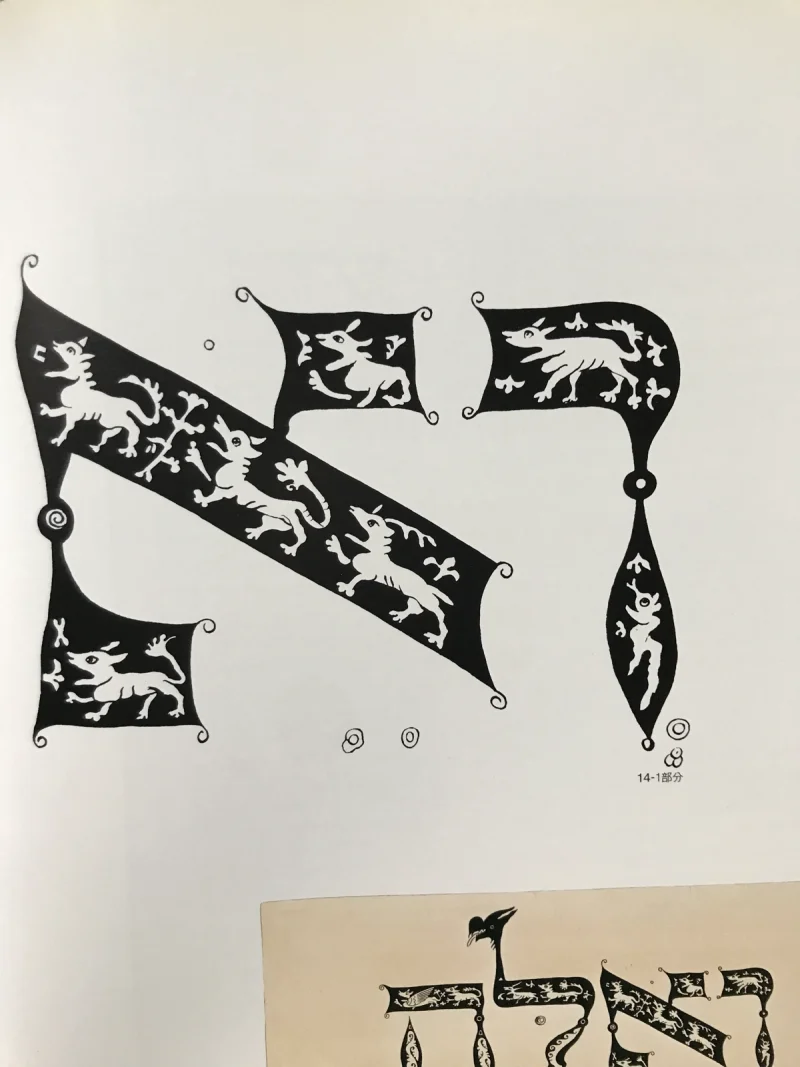

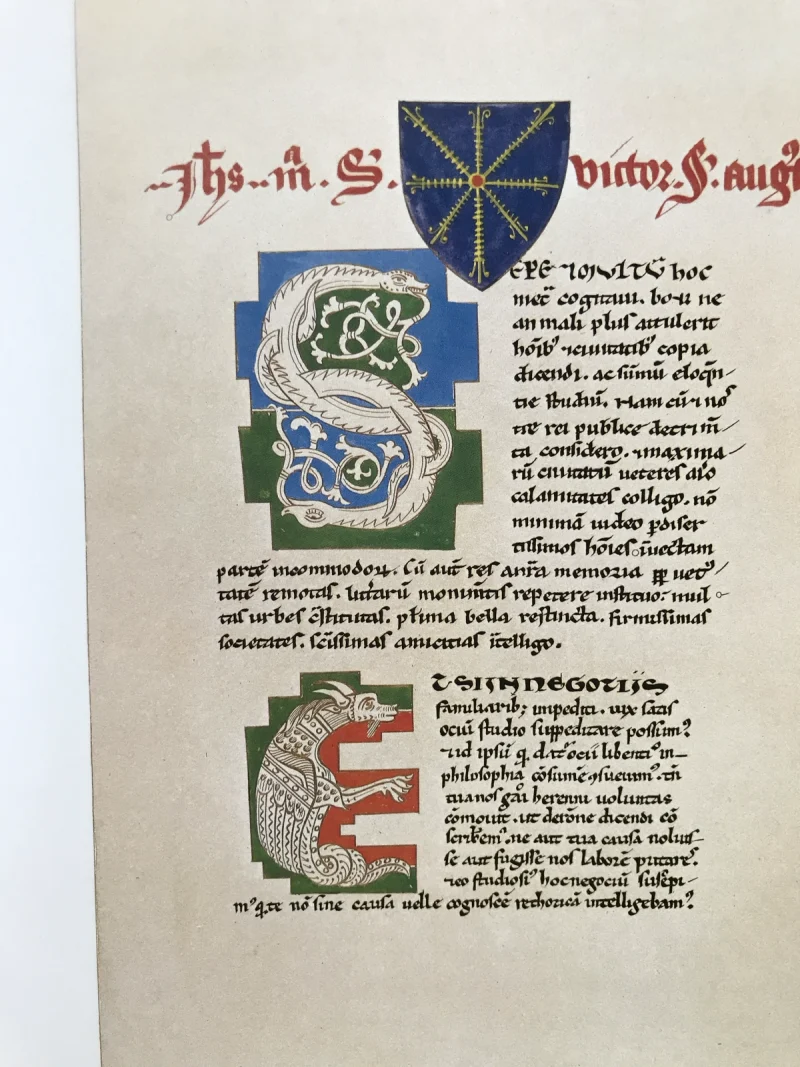

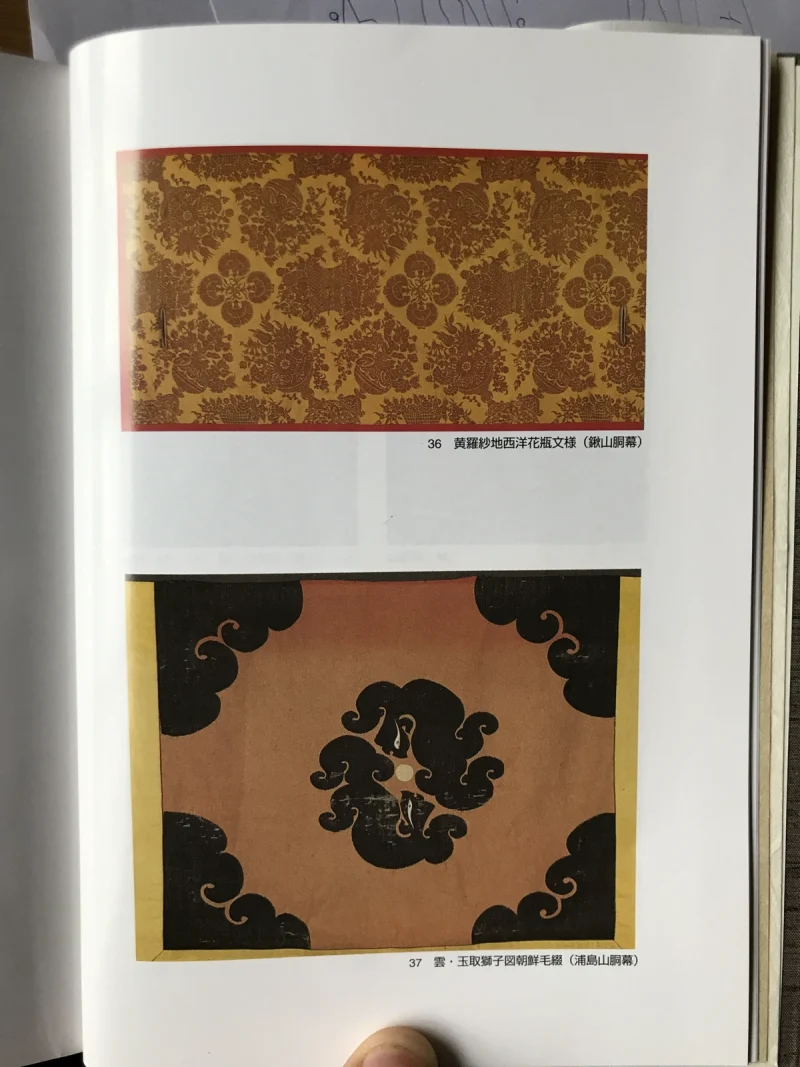

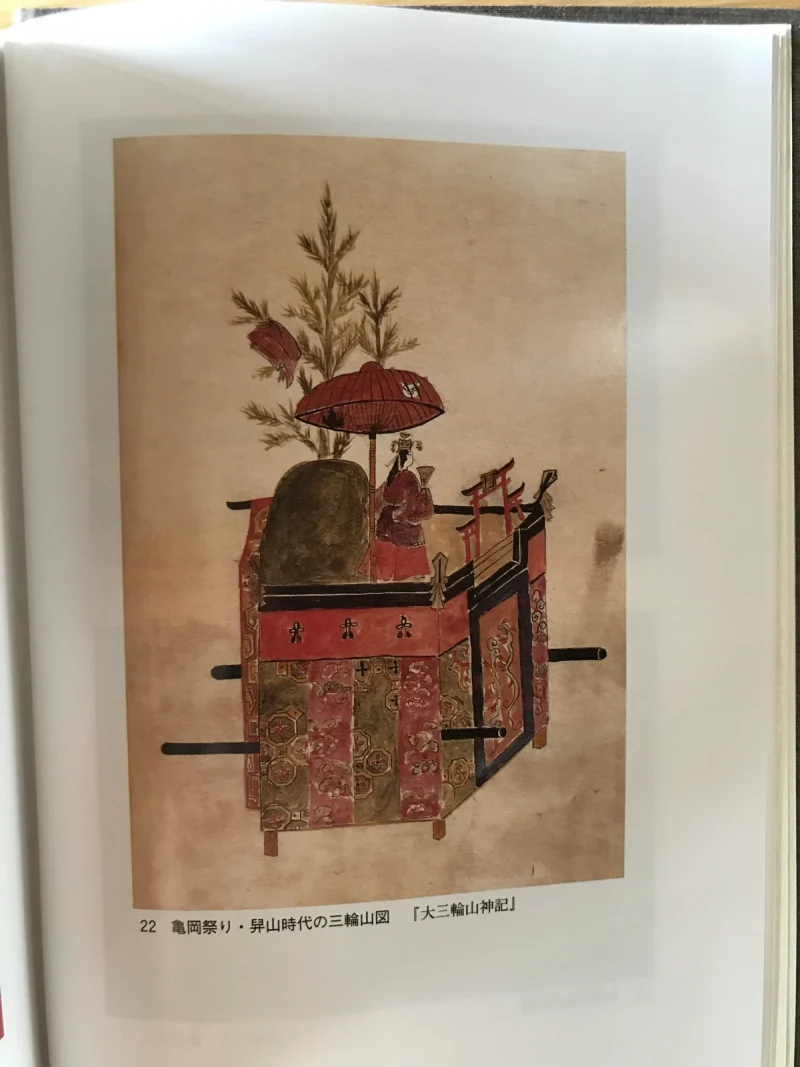

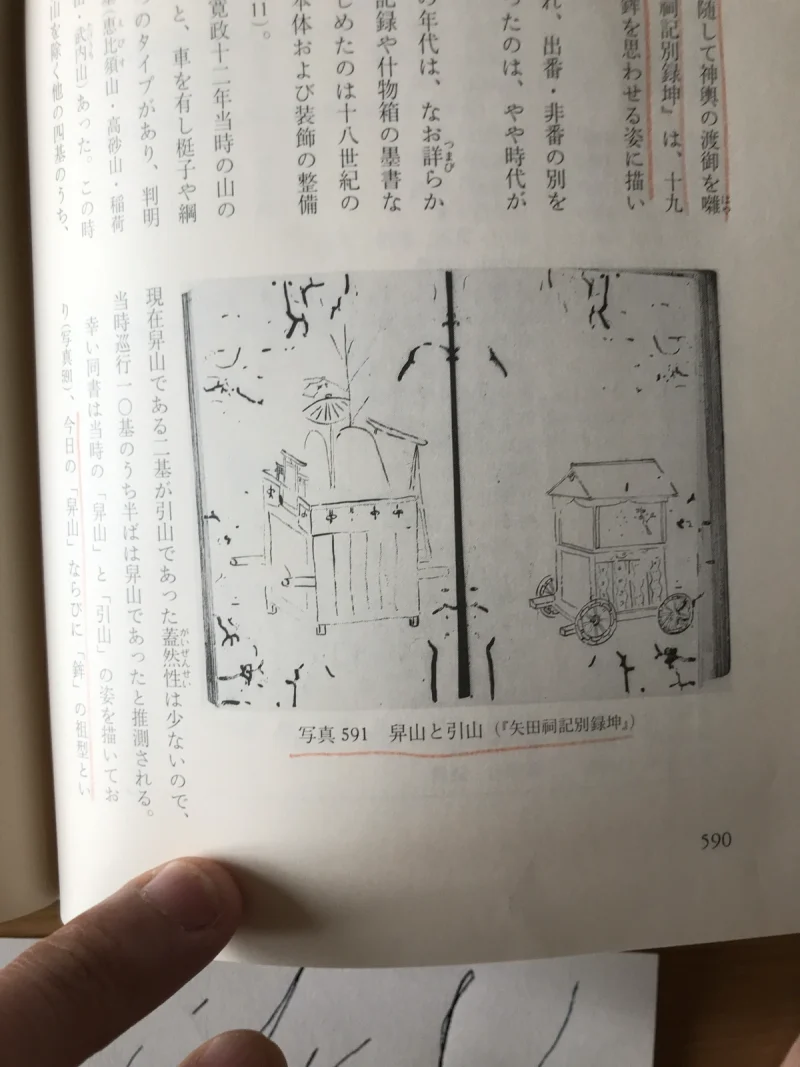

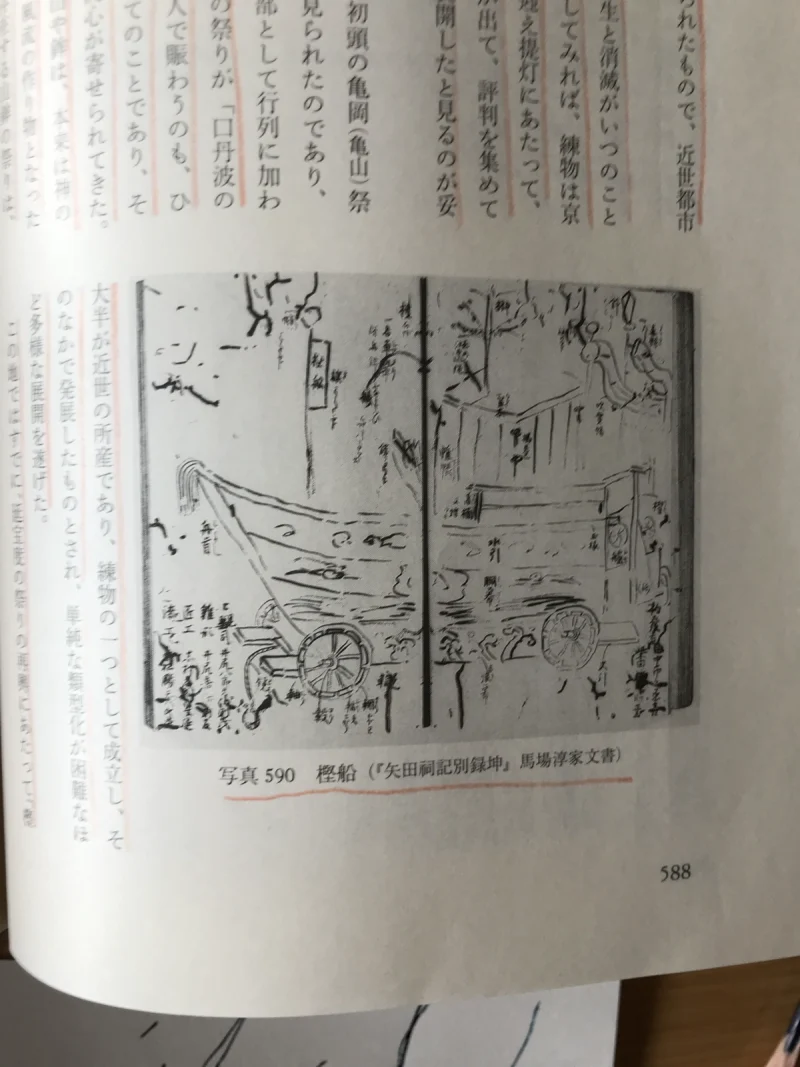

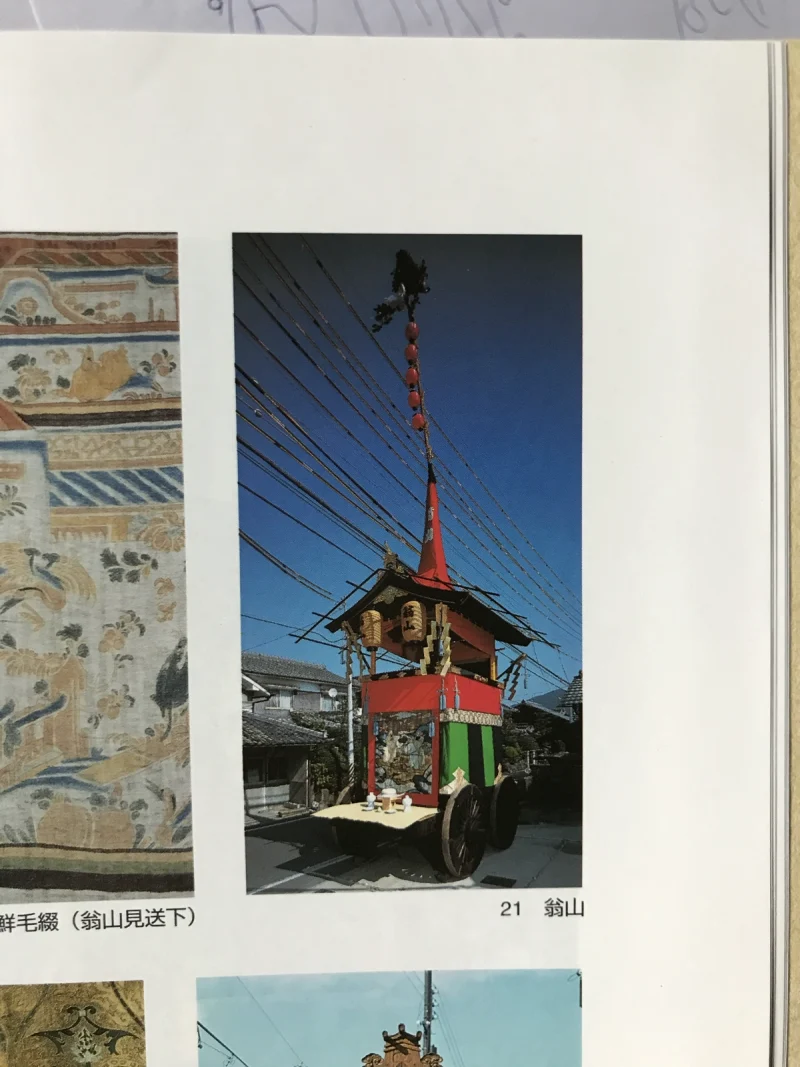

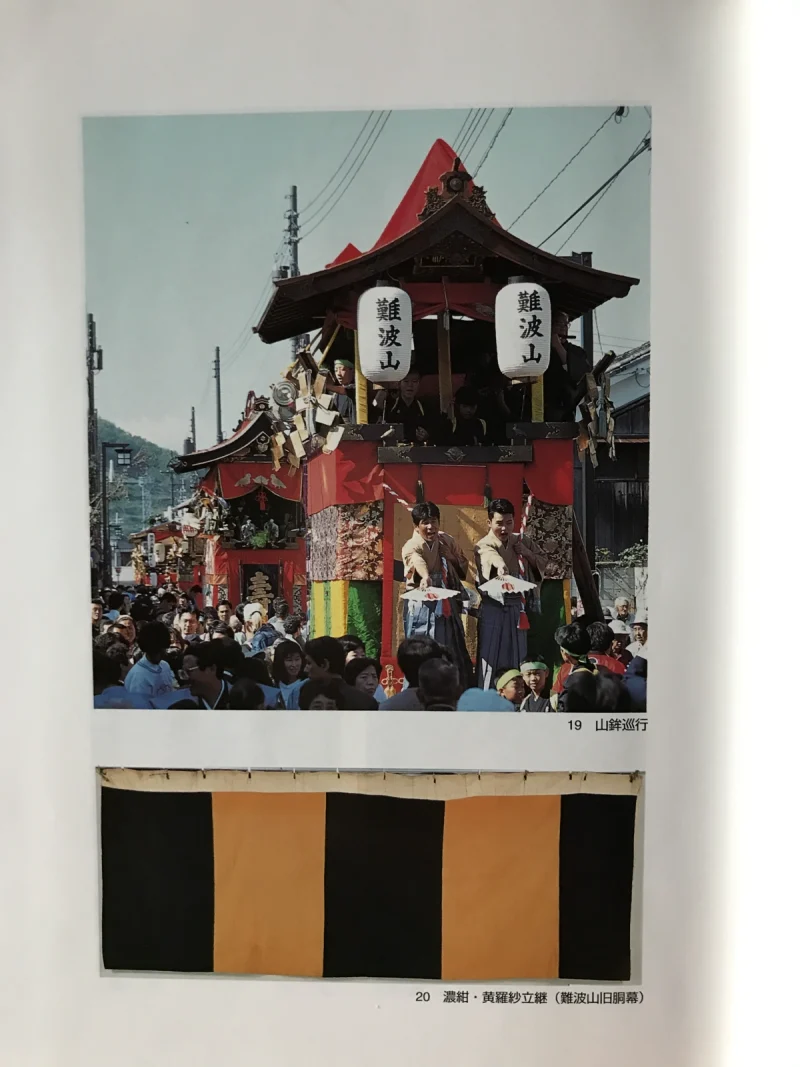

今後の制作では「地理的要因から発生した亀岡の文化とその流れ」を文献や図版から探り、造形へ展開していく。鶴岡真弓氏が『京都異国遺産』(平凡社)で論じたように、京都の文化財にはヨーロッパから中東、中国を経由して日本に入り混じり合った表現が見られる。亀岡市では山鉾が好例である。プロジェクト名「A HAMLET」がシェイクスピアから引用されているように、土地に根ざしながらも多様なものと混じり合う表現を目指したい。

–

A Consideration on Symbolization

In visualizing the symbols of this project, there are broadly three interwoven elements.

The first is the culture of Kameoka, shaped by geographical factors.

The second is tile-making—formerly the livelihood of the Yamamoto family—and the clusters of factories and houses connected to it.

The third is the trajectory of this project itself.

These three lines, when traced, move progressively toward the present〈Fig.1〉. Viewed from another perspective, as a cross-section of the land where the houses stand, they overlap like strata〈Fig.2〉.

Human activity is like a ball once thrown: it begins at some point, and over time it traces a line, heading toward some unknown place. The “now” in which we live is the very edge of that line. What comes next, or what ought to come, can only be inferred from the flows of the past.

Looking back〈Fig.2〉, it is common for different cultures, religions, and political ideologies to press down upon the lives of those who dwell in a place. What matters is whether such contact manifests as violent domination, or with attentiveness and proper conduct. In Japanese folklore and mythology, stories of new gods being born show this dynamic. Marebito—guest deities arriving from afar—were, I believe, intellectuals exiled from the continent who came to Japan. When they attempted to settle, native gods posed questions, to which the newcomers responded with gifts or songs; in return, they received a goddess as wife, and children were born. Through such mixing, our ancestors are thought to have acquired technologies such as weaving, herbal medicine, calendrics, gunpowder, and iron-making.

In A HAMLET, we are the ones overlaying. It is desirable that we engage constructively with those who have lived here before, and with the folklore of the land, so that new culture may emerge. This also aligns with my own concern: how to connect “design”—a loanword left untranslated in architecture—not with economy, but with culture.

The method I propose is to grasp the three lines at their edges and interlace them to create a visual symbol. The model is basketry. As with weaving an awaji knot from akebi vines, alternating two strands up and down, what were once loose lines suddenly lock into place, and a surface rises. In this way an image (a figure) is formed〈Fig.3〉.

When visiting Kohaku-gai, a prior case study, Mr. Kawabata (one of the project owners, a real estate agent) remarked: “Real estate completely changes once tenants move in.” A building is considered complete when construction ends, but once inhabited, it is used in ways entirely unforeseen by its design, and this usage seeps into interiors and exteriors. In collective housing, the character of the community is determined by tenant relations: whether it becomes closed, like a condominium association, or develops an autonomous atmosphere, like Kohaku-gai, with self-organized outreach and dialogue. Such outcomes depend greatly on the quality of the building and the relationships among residents, and are not easily reproduced by design〈FW01〉〈FW02〉.

Tile-making, by contrast, involves gathering and refining soil, mixing it with water, kneading it into clay, shaping and drying it. In this state it is fragile: rain would dissolve it. Only when fired in flame does it harden, repel water, and become tile. During a site visit, I learned that soil excavated for tile had lowered the ground level around houses; that ridge tiles were secured with the same clay used in their making; and I was shown the wave patterns and family crests impressed in them. What surprised me most was that Mr. Yamamoto, the owner, personally took part in construction. During dismantling, clay from roofs and walls was stripped off, not discarded but refined again and reused as material. In the exterior landscaping, a small grove was planted, with a hearth bed lined with clay once destined for tiles. I was able to join briefly in the work, taking part in the making of A HAMLET. That the owner works alongside builders, and that soil and tile-making elements from the land itself are incorporated, ties the project closely to livelihood and place.

When compared with tile-making, a building resembles unfired tile. Just as unfired clay, shaped and dried, dissolves when touched by water, so a building cannot stand on its own. Buildings are never built without purpose—whether to dwell, to keep animals, or to enshrine. When inhabited or used, the place is transformed into something else. As unfired tile changes character when subjected to fire, a building is transformed by its users. Clay is the building; flame is its user〈Fig.5〉. Moreover, as a tile spends far longer atop a roof repelling rain than in its making, so too architecture spends far longer in habitation than in construction. Even if the original owner departs, children or strangers may repair and continue living there. The quality of the community shifts dramatically depending on who lives within, and the task of adjustment continues. This process resembles the “management of fire.” I came to think that by reflecting on fire management, one can think through this project.

A folktale from Yamagata’s Okitama region, Nezumi Jōdo (“The Mouse Paradise”), includes a striking term. It is considered a prototype of the Omusubi Kororin tale and exists in many variants nationwide. In the Yamagata version appears the figure of the “fire-borrowing hag” (himorai-baba). Notes describe her as a useless old woman who let her hearth fire die and had to beg fire from a neighbor. In earlier times, fire could not be started with a switch as today. To kindle flame from nothing was arduous; thus, when going out or sleeping, people banked the fire, never letting it die, so it could later be fanned back to life for warmth and cooking. To fail at fire management was a mark of disgrace.

In A HAMLET, the project owners are chiefly responsible for fire management—that is, adjusting the relationships among residents and the community. Yet residents, too, must cultivate this capacity. In running shops or living there, they must not only mind themselves but keep A HAMLET’s flame alive. From this perspective, it is fitting to symbolize “fire” as a shared language between users and organizers. To build architecture, media, and visual identity is to create a hearth bed (hodo) and to kindle a seed flame. Looking further ahead, a phase of “sharing the flame” (bunka) may emerge: flames kindled now may amplify, passing to others as residents depart, or perhaps those who let their fires die—the “fire-borrowing hags”—may come seeking a new one. In such cases, we must ask what form architecture, media, and visual identity should take, and consider them through the lens of fire management〈Fig.6〉.

In future making, I intend to explore forms grounded in “the culture of Kameoka born from its geography and its flow,” drawing on literature and visual sources. As Professor Mayumi Tsuruoka has argued in Kyoto Ikoku Isan (Heibonsha), Kyoto’s cultural properties reveal expressions that arrived via the Silk Road and other routes, from Europe, the Middle East, and China, and merged in Japan. In Kameoka, the yamaboko floats are a fine example. Just as the project name A HAMLET cites Shakespeare, I hope to create something that rises from the ground of this land, yet mingles with diverse influences.