Preface.

–

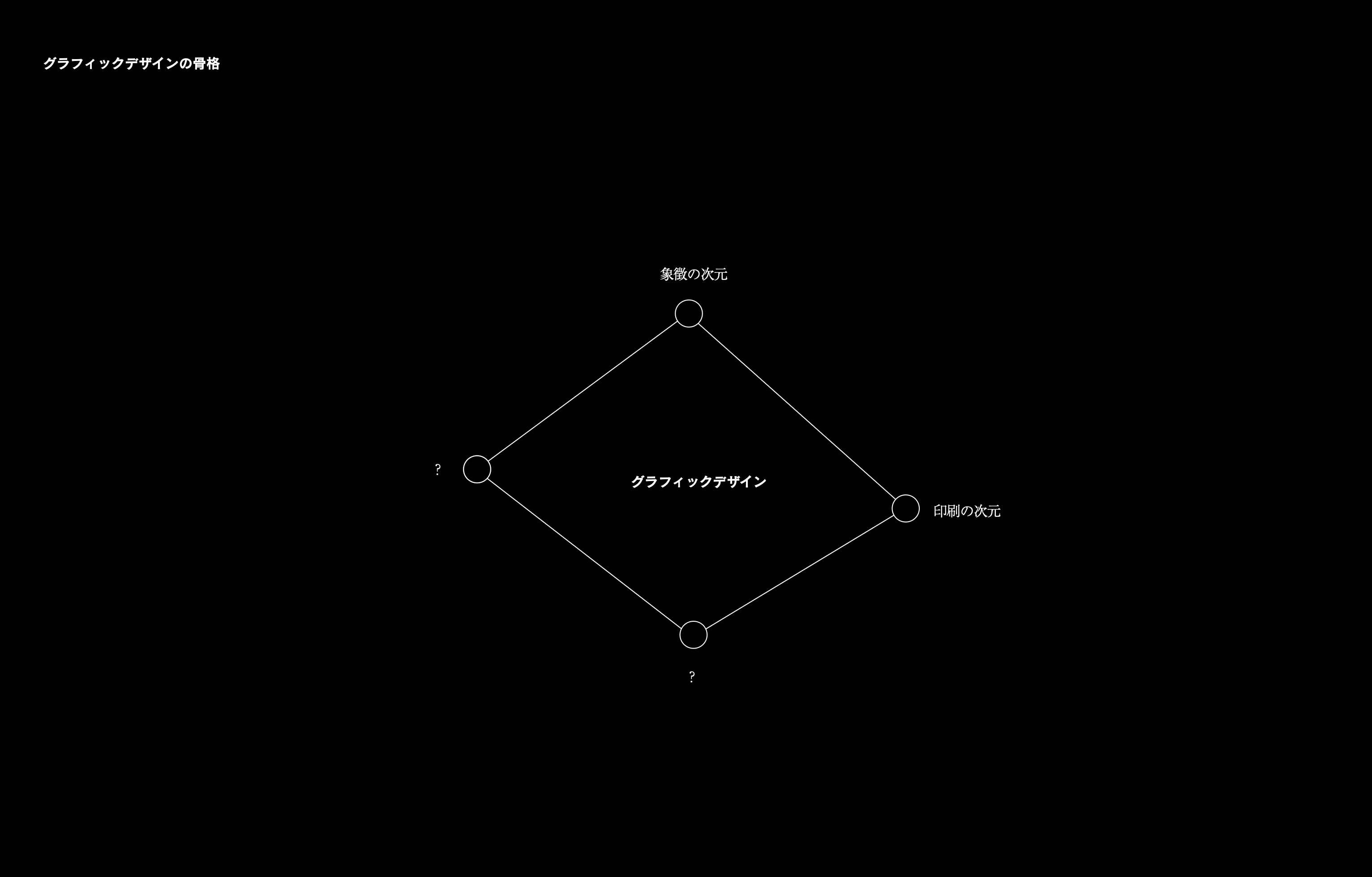

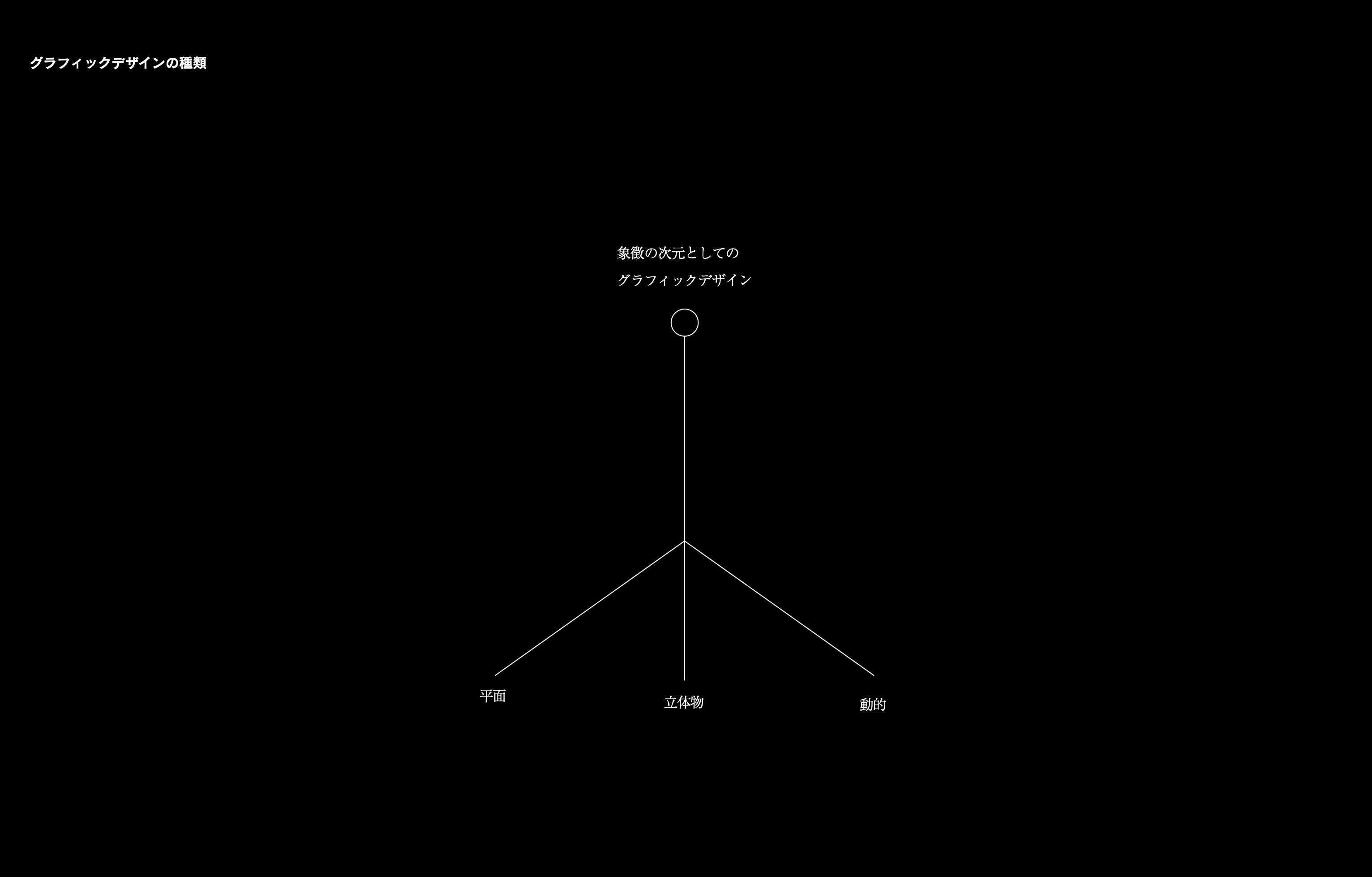

グラフィックデザインの中にもいくつかの次元が存在する。

頭でイメージしたものやクリエイティブ・アプリケーションで制作したデータを現実世界に存在させる「印刷の次元」だ。他にもいくつかあると思うが、まず思いつくのは「象徴の次元」。今回のプロジェクトはこれが主題となる。

まずはわかりやすくまとめてあるものを引用したい。

アメリカ先住民のポーニー・インディアンは、小屋を建てて季節儀礼を行います。その小屋の柱には、方角ごとに4種の木が使われます。木はそれぞれ違った色に塗られます。南西方向には白いポプラ、南東方向には赤いネグンドカエデ、北東方向には黒いニレ、北西方向には黄色いヤナギが置かれます。方位はそれぞれ季節を象徴しており、季節が集まって年となります。こうした分類は、ポーニーの人たちにとっての方位=空間概念と季節=時間概念の仲立ちをします。

こうした分類体系は分類のためだけにあるのではなく、空間と時間を結びつけ、宇宙の連続性を表現しています。それは象徴の次元で現実をいったん解体した上で再構成し、全体像を作り上げる手段になります。

——奥野克巳(2023).はじめての人類学.講談社〈講談社現代新書2718〉

このポーニー・インディアンの事例は「象徴化」を非常に良く表している。デザイナーにわかりやすい言葉で言い換えるとロゴマークなどのシンボルマークやタイプフェイスを制作するプロセスで行われている行為だ。クライアントの企業の創業や事業の拡大縮小、今度の事業展開、取締役や従業員のライフヒストリー、サービスや商品構成などといった様々なものが絡み合った複雑なものをヒアリングし、それを「象徴の次元」へ降りていって、単純な図形と字形に落としていく。その過程で行われいるのが「それは象徴の次元で現実をいったん解体した上で再構成し、全体像を作り上げる手段」である。

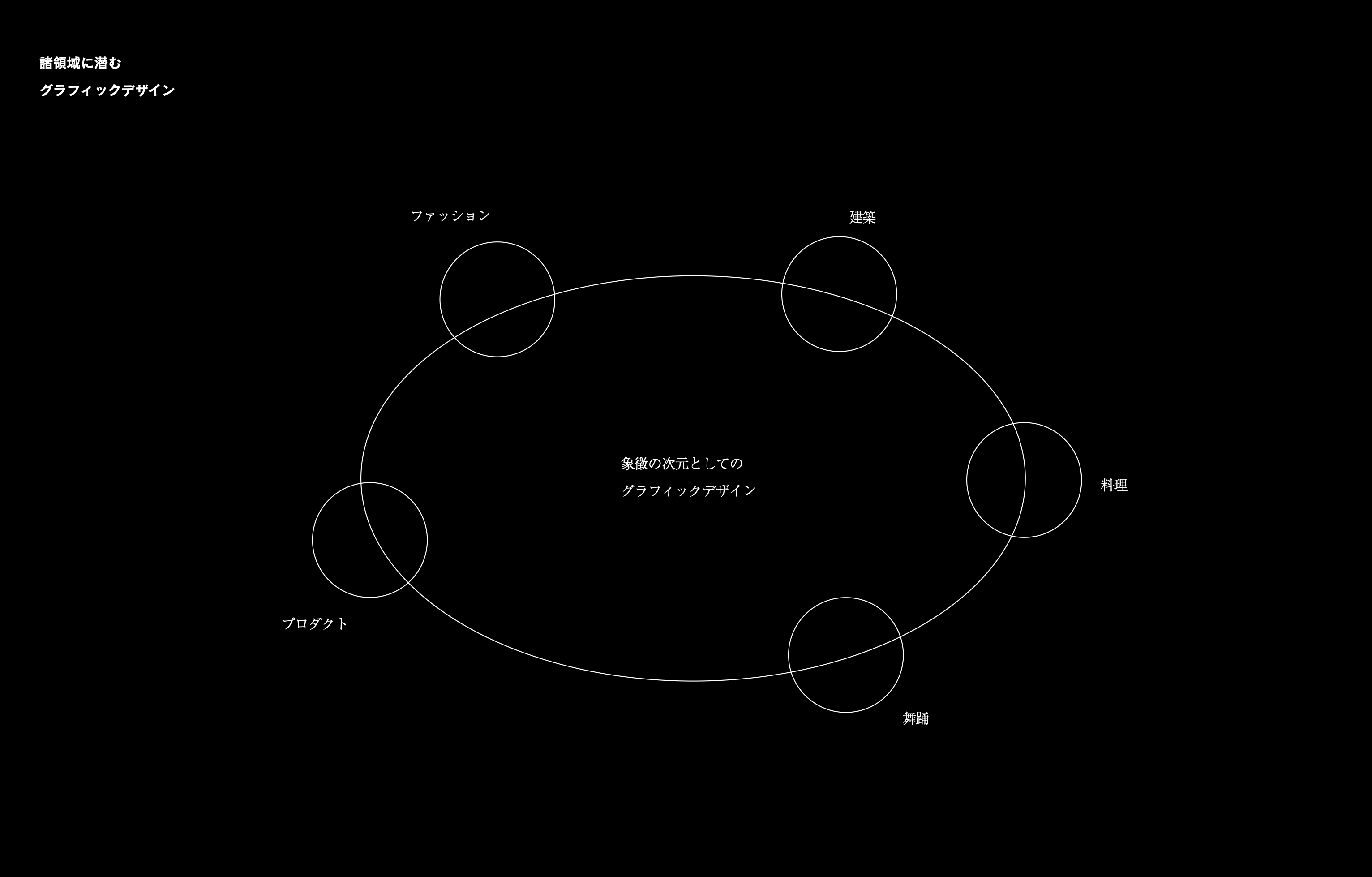

そして、ポーニー・インディアンの事例を見る限り、平面にとどまる次元ではない。柱や小屋といった立体物や空間、おそらくダンスなどのパフォーミング・アーツにも象徴の次元は通底しているだろう。ダンスを能や舞踊といった儀礼に置き換えてみるとファッション、料理、プロダクトにもまたがっているように感じる。象徴の次元は制作にまつわるすべての行為に横断しているようだ。

グラフィックデザイン領域ではシンボライズという領域が存在するくらい「象徴化」が体系化されてきた一方、友人の建築家や大工に聞く限り、建築や施工の領域では「見栄え」「見た目」といった言語に「象徴化」が内包されている。いまいち体系化されていないようであった。これをそのまま鵜呑みにするならば、建築や舞踊といった制作の諸領域を下支えしているのは「象徴の次元」としてのグラフィックデザインであるといえる。

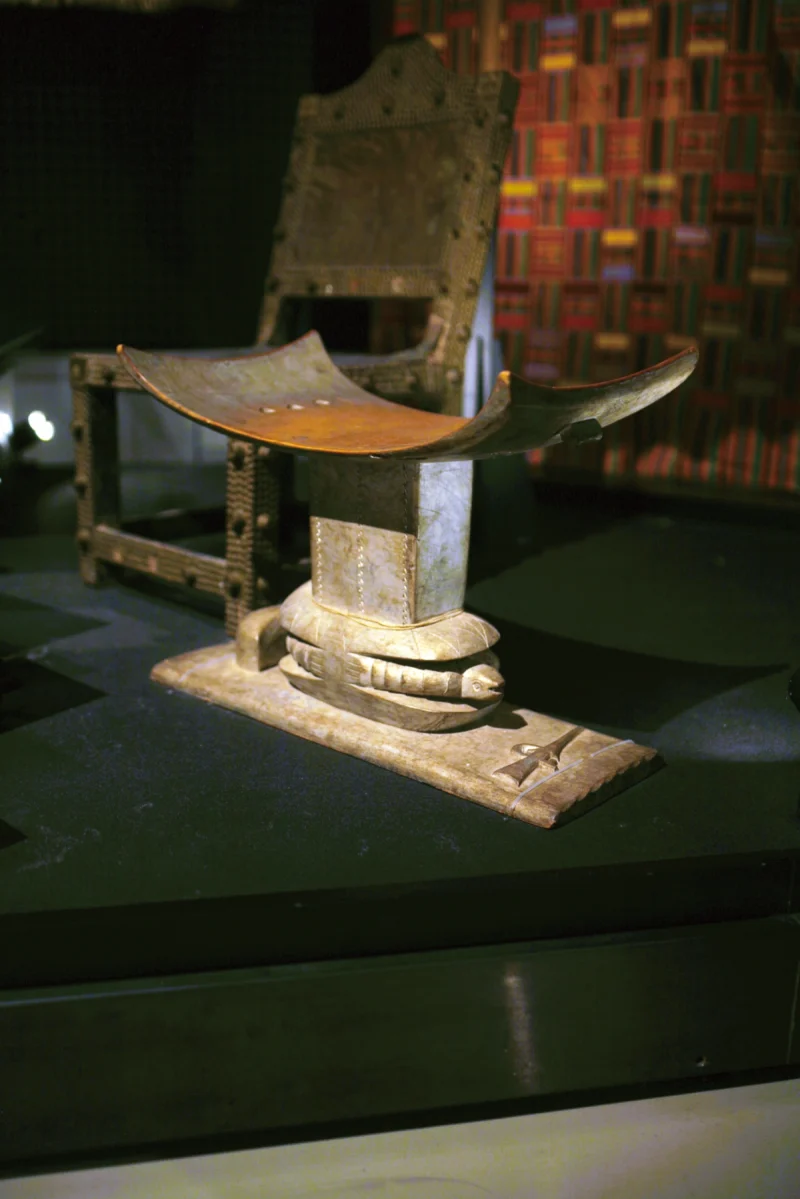

そうであるならば、試しに「象徴の次元」から椅子を作ってみようとおもった。その結果、出来上がったのがこのANIMAL FURNITUREである。

–

There are several “dimensions” within graphic design.

One is the dimension of print—the dimension in which images formed in the mind or data produced in creative applications are rendered into physical existence in the real world.

There are others as well, but the one that comes to mind now—and the theme of this project—is the symbolic dimension. To begin, let me cite a concise account.

The Pawnee, a Native American people, build a lodge to conduct seasonal rites. The lodge’s posts use four kinds of wood aligned to the cardinal directions, each painted a different color: white poplar in the southwest, red box elder in the southeast, black elm in the northeast, and yellow willow in the northwest. Each direction symbolizes a season, and the seasons together compose the year. This system mediates, for the Pawnee, the relation between direction (as a spatial concept) and season (as a temporal concept).

Such classificatory schemes are not for classification alone; they bind space and time and express the continuity of the cosmos. They provide a means of first dismantling reality within the symbolic dimension and then recomposing it to form a whole.

— Katsumi Okuno (2023), Hajimete no Jinruigaku [An Introduction to Anthropology], Kodansha (Kodansha Gendai Shinsho 2718)

This Pawnee example illustrates “symbolization” exceedingly well. In terms familiar to designers, it is the very operation performed in creating symbol marks—logos and typefaces. We listen for the client’s complex entanglements—founding history, expansions and contractions of the business, upcoming ventures, the life histories of directors and staff, the makeup of services and products—and we descend into the symbolic dimension to reduce them to simple shapes and letterforms. What happens in that process is precisely “a means of dismantling reality once within the symbolic dimension and recomposing it to form a whole.”

And, as the Pawnee case suggests, this dimension does not stop at the flat plane. The symbolic dimension also runs through three-dimensional objects and spaces—posts, lodges—and likely through performing arts such as dance. If we recast dance as ritual—Noh or other forms—one senses it extends across fashion, cuisine, and product as well. The symbolic dimension appears to cut across every act of making.

Within graphic design, symbolization has been systematized to the point of being a distinct subfield. By contrast, judging from conversations with architect and carpenter friends, in architecture and construction the notion of “symbolization” tends to be folded into everyday terms like “appearance” or “look,” and seems less thoroughly theorized. If we take that impression at face value, then it is graphic design—as the symbolic dimension—that undergirds other making disciplines such as architecture and dance.

If that is the case, I wondered whether one could make a chair from the symbolic dimension. The result is this ANIMAL FURNITURE.