Essay.

–

山形滞在制作記

山形県大江町、2024年10月4日。音楽家の角銅真実さんと編集者の永江大さんが私の工房にやってきた。なにやらアルバムのリリースツアーに際してグッズをつくって欲しいとのことだった。実は彼らと仕事をするのは、はじめてではない。数年前に超短編アニメーション映画をつくったときの仕事仲間だ。アニメーションといってもコマ撮りという非常に古典的な手法だった。採集をモチーフとして世界を理解することをテーマに、脚本や登場人物や背景などの人形や美術素材を私や永江さんたちでつくった。動かしてもらうのはアニメーターの友人にお願いし、そこまでのつくり方を1日で教えてもらった。教えてもらったというと語弊があるかもしれない。私たちがああでもない、こうでもないと話しているそばに彼が立っていて時折、物語やプロットを描く要点みたいなものを指摘され、それに応答するような形だった。稽古に近いと思う。

背景に山が登場しそうなことは決定したので、まずはみんなで山のなかに入り、そこにあるものを採集した。いい感じの樹皮を持つ樹を見つけたら大きな紙を押し付け、根元の腐葉土で擦り付けフロッタージュしたり、森をしばらく歩いて沢に出たときには石をひろい、絵の具をつくったりした。民話の「おむすびころり」のようにプロジェクトが転がり始めてなにかに決着がつくと別のなにかが転がり始めるようなつくり方だった。

同じようなつくり方で、角銅さんにはアニメーションの音楽をつくってもらった。音を採集する機会をひらき、東京の品川で参加者とともにフィールドレコーディングを行った。音そのものを探したり、音が鳴りそうなものを探す。私は趣味がキノコ採りなので森をよく見ている。基本的に目や鼻で探している。耳はクマの唸り声や鳥の鳴き声、風の音、沢の音などの脅威や環境を認識するために使うことが多かった。しかし、音の採集では目で鳴りそうなものを探し、近づいて鳴らしてみて良さそうな音かどうか耳で判断した。目と耳の使い方が普段と逆さまであった。むしろ目を閉じたほうが採集物が見えてくる。アスファルトで舗装されたビル街で目を瞑ると近くの街路樹で鳥がピーピー鳴いていた。よく見ると鳥の巣があることに気付く。風で揺れる消火栓の金属チェーンは、キーンキーンと自然界では聞き慣れない高い音を出していた。目で見る品川の風景と耳で聞く品川の風景音はだいぶ印象が異なっていたのだった。

そうやって集めた音の素材を角銅さんへ渡し、つくってもらったのが『Digest The World もうひとつの臓器』の音楽であった。みなさんもぜひ見て欲しい。

*

彼らはグッズの手がかりを採集しに来たのであった。私の工場(こうば)は印刷や製本の機械が並んでいる。そこでなにか手を動かしながらどんなグッズをつくるか考えるのだ。

機械を動かしながら扱える技術の説明をしていく。一番はじめに工場にやってきた箔押し機、次にやってきた輪転機、大判の石版印刷機、紙折機、筋付け機、紙孔機、断裁機、中綴じ機、リング製本機、カラス切機。印刷から製本、製函の機械たちだ。

言葉で説明してもわかりづらいので、とりあえず白紙のページを束ねてみることにした。要はノートをつくる。まずはヤレ紙で角銅さんが好む判型をいくつか出してもらった。バッグに入れて持ち歩くなら。ピアノに乗せて使うなら。いくつかのシチュエーションに沿って判型が出てきた。それに加えて工場にある大判紙からの取り都合を考慮し判型を定めていった。取り都合というのは大きな紙からなるべく無駄が出ないように素材を切り出すことをいう。例えば、40cm四方の板紙があった場合、表紙として縦30cm、横20cmを切り出すと2枚しか取れないが、判型を見直して20cm四方とすると4枚取れる。だが取り都合ばかり考えると製紙業の規格に沿うことになるのでありきたりな寸法になってくる。常に空想した形と現実的な取り都合との間で判型は揺れ動くのであった。

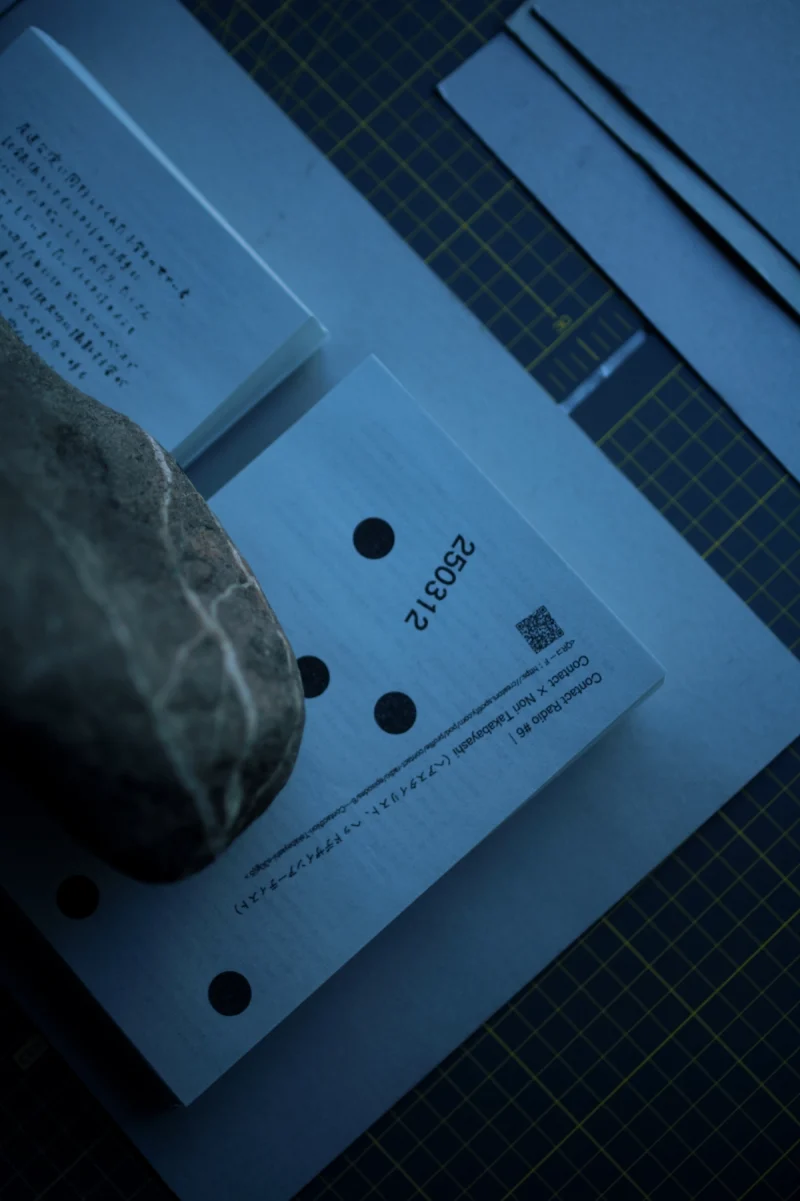

工場にある機械のなかでは紙孔機が気に入ったようだった。紙孔機は紙に穴を空ける機械だ。私の工場では直径3mmから直径7mmまでの穴を空けられる。さきほど表紙用に切り出した2.5mm厚の板紙をドリルの下に置き、スイッチを押すとドリルが下がってきてキュルキュルと紙と金属が擦れる音を出しながら穴を開けていく。ドリルが上がると板紙をひょいと拾い上げ、穴からこちらを覗き込んでいた。

*

山形には「鼠浄土」という話がある。「おむすびころり」の原形となった話で日本各地に同じものが点在している。基本的に話の骨子は一緒なのだが、穴のなかに入った後の顛末が異なるようだ。鼠の村があったり、蔵のなかに宝があったり、鯛をご馳走されたりと各地の風土が織り込まれ、ひとつの話にバリエーションを与えている。山形版では鼠たちが餅つきをはじめ、ジイさんに餅を振る舞うのだった。実に山形らしい展開だ。山形では餅の振る舞いといって街場で臼と杵を使って餅を搗いていると、その音に誘われてどこからともなく人が集まってくる。子ども、父母、ジジ、ババ、中高生、大抵の人が餅をもらいにやってくるのである。そして、餅を受け取るとベンチや階段といった腰をおろす場所を探し、自ずと餅つきを囲むように座り始めるのだった。思い思いに餅を頬張る姿は幸福感に満ちている。

話のタイトルに「浄土」が付くように穴の先は向こう側の世界であった。「穴」は私たちの世界から向こう側の世界へ近づけるギリギリの境界線である。穴を自由に往来する「鼠」や地面から湧き出る「水」は向こう側の属性を帯び、不思議な力があると考えられていた。つまり私たち人間が鼠の気まぐれで向こう側の世界に迷い込んだ話が「鼠浄土」だ。鼠たちは私たちの世界と向こう側の世界をつなぐ案内人なのである。

*

角銅さんが輪転機(簡易印刷機)を使おうとして蓋を開けた。機械が起動を始め、製版の準備運転に入った。グオングオンと低い音を出し始める。蓋を開けたところには大きな穴が空いていて、その向こう側から緑色の光が溢れてくる。しだいに光は強くなり、私たちを飲み込んでしまったのだった。

しばらくすると目が慣れてきた。あたりを見回すとそこは「浄土」でもなんでもなく私の工場であった。

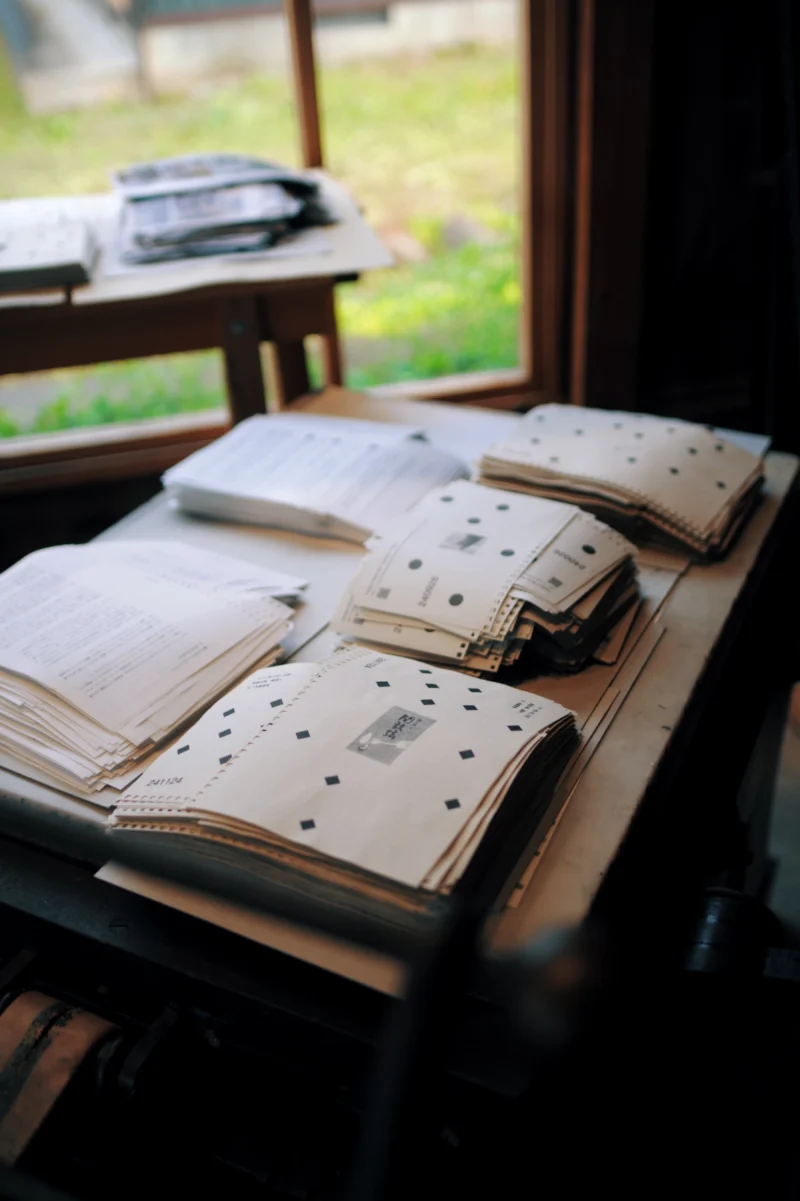

グッズの見本として3種類の穴の空いたノートが完成した。ページをめくったり、穴から向こう側を眺めたりしながら今回の滞在制作を振り返っていると「今日は、私が世界を音楽として見ているように、世界を印刷として見ることができるとわかりました」。ああ、なるほど、たしかにそうかもしれない。

一度、輪転機の穴を通ってしまった私たちは印刷の世界に迷い込み、それまでいた世界へ帰ってこれずにいるのかもしれない。

–

Yamagata Residency Journal

Ōe Town, Yamagata Prefecture, October 4, 2024. Musician Mami Kakudō and editor Dai Nagae came to my workshop. They asked if I could create goods to accompany the release tour of an album. It wasn’t the first time I had worked with them. Years earlier, we had collaborated on a very short animated film. Despite being an animation, it was made using the highly traditional method of stop-motion. With “gathering” as its motif and “understanding the world” as its theme, we created the script, characters, and stage props together—myself, Nagae, and the others. The animation was then moved by a friend who was an animator. He taught us the basic method in just one day, though “taught” might not be the right word. He stood nearby as we debated this and that, occasionally pointing out key aspects of storytelling and structure, to which we would respond. It was more like training than instruction.

Since it had been decided that mountains would appear in the background, we all first entered the mountains and began gathering what we found there. When we came upon a tree with interesting bark, we pressed large sheets of paper against it and rubbed with humus to make frottages. When we reached a stream after walking through the forest, we picked up stones to make paint. The process unfolded like the folktale Omusubi Kororin: as soon as one thing reached resolution, something else began rolling forward.

In much the same way, Kakudō composed the music for the animation. We opened opportunities to “gather” sounds, holding field recording sessions with participants in Shinagawa, Tokyo. We searched not only for existing sounds but also for things that might make sounds. I usually forage mushrooms as a hobby, so I am accustomed to observing forests with my eyes and nose. My ears are typically used to detect threats or environments: the growl of a bear, birdsong, wind, or running water. But in sound gathering, I used my eyes to find objects that seemed like they might make sounds, then drew near and made them resonate, judging with my ears whether the sounds were good. My use of eyes and ears was reversed. In fact, closing my eyes often made the collected material more vivid. In the asphalt-paved city, when I closed my eyes, I could hear birds chirping in a roadside tree and discovered a nest. A fire hydrant’s chain rattled in the wind, producing an unnaturally high metallic sound. The landscape of Shinagawa as seen with the eyes was quite different from the landscape of Shinagawa as heard with the ears.

We handed these gathered sounds to Kakudō, and the result was the music for Digest The World: Another Organ. I hope everyone has the chance to listen.

*

This time, they had come to gather clues for goods. My workshop is filled with printing and bookbinding machines, and the idea was to think with our hands while moving the machines.

As we set the machines in motion, I explained their functions. First came the foil stamping press, then the rotary press, the large lithographic press, the folding machine, the creasing machine, the punching machine, the guillotine cutter, the saddle-stitching machine, the ring binder, the trimmer. Machines for printing, binding, and boxing.

Words alone made little sense, so we decided to bind blank pages together—to make a notebook. Kakudō suggested several preferred formats: small enough to fit in a bag, or large enough to sit on a piano. We compared these with the dimensions of available stock paper, adjusting formats so as to minimize waste. For instance, from a 40cm square sheet of board, cutting 30 × 20cm covers yields only two pieces, but revising the format to 20cm squares yields four. Yet too much attention to efficiency risks being trapped by standard industry sizes, leading to ordinary dimensions. The design constantly swayed between imagined form and practical economy.

Among the machines, Kakudō seemed most taken with the punching press. This machine drills holes in paper, ranging from 3mm to 7mm in diameter. We placed a 2.5mm-thick cover board beneath the drill, flipped the switch, and listened as the drill descended, squealing as it bored through paper and metal. Lifting the board, we peered back at each other through the new hole.

*

Yamagata has a folktale called Nezumi Jōdo (“Mouse Paradise”), the prototype of Omusubi Kororin, with variants across Japan. The core is the same, but the outcome after entering the hole differs: a village of mice, a storehouse of treasure, a feast of sea bream. Each reflects the local culture. In the Yamagata version, the mice pound rice cakes and serve them to the old man—a fittingly local detail. In Yamagata, when mochi is pounded in town with mortar and pestle, the sound draws people from everywhere—children, parents, grandparents, students—until all gather to receive a share. Sitting on benches or steps, they encircle the pounding, each savoring their mochi, a scene filled with joy.

As the title suggests, “Paradise” lies on the far side of the hole. The hole is the fragile boundary between our world and the other world. Mice, who freely pass between, and water, springing from the earth, were thought to carry the qualities of that other side and to possess mysterious powers. Nezumi Jōdo is thus a tale of humans wandering into the other world at the whim of mice, who serve as guides between the two realms.

*

Kakudō opened the lid of the rotary press. The machine began its preparatory run, groaning in low tones. Through a great hole beneath the lid, a green light poured out, growing brighter until it engulfed us.

When our eyes adjusted, we found ourselves not in paradise but back in my workshop.

As samples, we completed three notebooks, each with different holes. Flipping their pages, peering through the holes to the other side, we reflected on the residency. “Today,” Kakudō remarked, “I realized that just as I usually see the world as music, I could also see it as printing.” Yes, perhaps that is true. Having once passed through the hole of the rotary press, perhaps we had wandered into the world of printing, unable to return to the world we had left behind.